|

|

Rancho Camargo

A High School Teacher

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Hector Moroyoqui Juzcameya

Rancho Camargo, Sonora (3/30/02)

DB: When and where were you born?

I was born in 1972 on the 21st of January in the city of Navajoa. I was born in the Social Security Hospital. Thank God, during that time, my father was able to receive treatment there, even though he was a field worker, because his boss signed him up for the whole family. During that time we lived in a town, near Nachuquis, called Navolato. It was very close to the Escuela Normal del Quinto, the teachers' training school. But we had to migrate from that community due to my health problems.

DB: Were you sick a lot as a child?

I was bed bound, in excruciating pain. I couldn't stand or balance myself. I couldn't hold anything in my hands because I was like a numb person. My grandparents on my mothers side recommended that they visit a currandera. After seeing many doctors, they still couldn't alleviate my pain, so they saw it as a final option. They brought me to Señora Angela. She told us that we should not return to the place we were living because the envy of people there would never permit us to be healthy. That's why we came to live in the community of Punta de la Laguna.

|

|

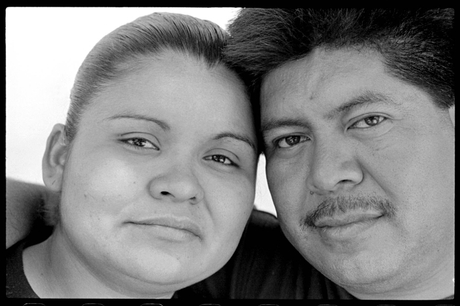

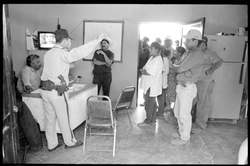

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 3/29/02 Hector Moroyoqui and Maria de Jesus Moroyoqui |

DB: Your parents are Mayo?

100%. My father's parents are originally from a different indigenous town called Jiton Queca. My mother is also 100% Mayo. My mother's parents are originally from a town that no longer exists, called Jitombrumo.

My grandparents, maternal and paternal, always spoke the Mayo dialect. Unfortunately, I can't speak it 100%. I'm not able to fluently express ideas in the Mayo dialect, but I do understand it, yes - almost perfectly. As children we were given the choice of which language to speak, and I grew up speaking Spanish. Now I regret not learning the Mayo dialect when I was young because knowing it would help me sustain my roots.

DB: What was your childhood like?

I lived in Navolato, a Mayo town, until my second year of primary education. The primary school was rural, for the indigenous community of Chucari, that belongs to the town of Chohowa. From there, I went to study third, fourth, fifth and sixth grade in Nachuquis community, at the Benito Juarez Federal Rural School. I lived like the other kids, in a peaceful atmosphere. But it was also a depressed atmosphere, because we always lacked money.

It was a very difficult test for us, but at the same it made us grow up faster, and gave us a different perspective on life. Because of our poverty, we always searched for a better way of living, of dressing, or even of eating. We really wanted to progress, and the lack of money made us understand that in life the only path to progress is education.

DB: Can you give me an example of the lack of money so that I can get a better idea of what it was like?

One clear example is lack of nutrition. Sometimes we would only eat twice a day, and only beans. When we had food we were very happy, but there were times when we didn't even have beans. Sometimes we would trade beans for roasted tomatoes, and that was the main course. We would eat it as if it was a shrimp cocktail. We would savor it because the hunger was intense.

I'm very proud of my father and my mother, because they never bullied us. They were always aware and attentive to their children. They did everything possible. They would go to the fields. They would bring beans, tomato, potatoes. As children we would accompany them so that we could all bring back more, to have sacred food in our home. Our house was aluminum and black cardboard without a floor. We didn't know what a refrigerator was back then. We had no cooler or stove, just a firewood stove. We didn't have electricity. There was no running water. There was no transportation. That childhood was very difficult, but at the same time it developed my character. It gave me more tools to be able to climb the big pyramids of life.

DB: What was your school like?

Every time my father took us to the field to work he would say, "If you don't want to be like me, you need to study. If you don't want to dress like me, you need to study. If you don't want to be tired all of the time like me, you need to study." That was a huge example that inspired me. I always hated working in the fields. I was never interested in it. I hated it. I did it because of the necessity, but not voluntarily. When I went to high school, the Technical Secondary School for Agriculture and Husbandry Number 45 de San Ignacio Coquirin, our classes were from 7 am to 2:30 pm Monday to Saturday. To be at school early, I would have to get up at 4 in the morning. At 4 am I'd get up to catch the bus at 5 am that took me to school Back then the bus charged 50 cents. Then a peso, and then one fifty. That was all that I had — a dollar or a dollar fifty — just enough for the transportation from my house to school. But I had no money to eat lunch, much less pay for another bus ride home. I had to walk or ask for a ride. If a friend had a bike, I'd ask if I could ride with him. So that was my three years of high school education. It was hard.

|

|

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 3/31/02 The hands of Angela Valenzuela Soto, that cured Hector Moroyoqui as a boy |

DB: How did you study at night?

Since we didn't have electrical light, we would put gasoline in little coffee bottles of coffee and through the lid we would put a piece of a blanket, and light it. That was what gave us light at night to study. That was the way I completed my academic preparation. I would get out of school at 2:30 pm and get home at around 5 pm when I would have to walk. I was young and restless. Before the sun went down, I would dedicate that time to playing soccer or baseball or just to simply run.

|

|

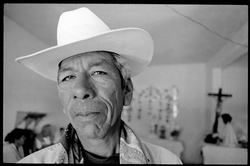

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 3/31/02 Angela Valenzuela Soto, a curandera |

DB: How did you decide to become a teacher and go to the Quinto Preparatory School?

I never thought that I would become a teacher. I wanted to become a lawyer, but our economic limitations would never allow me to go to a university. For me, that was only a dream. Later, my father had a boss who was an agronomist, and I liked that career. I took all of the exams to get into the Chapingo University in Ciudad Obregon, and passed them. Unfortunately, my mother did not want me to go, and said I was too young. I was only 15. That same year they gave exams to get into the Escuela Normal del Quinto. Back then the preparatory course there took seven years. So I went to Navojoa to take the exam.

Fifteen days later, we got the exam results. Many of my friends thought the test was easy and were sure they'd passed. I thought it was really hard, and wasn't sure at all. The surprise was that none of them got in except me. Out of the list of 100, I was ranked 18th. I cried, I was so happy. Now that I remember, my soul cries out to me that when someone wants to improve they can do it. [he cries]. I know that I have more obstacles today, but now I see them in a different way because I am prepared, thanks to my parents and God.

|

|

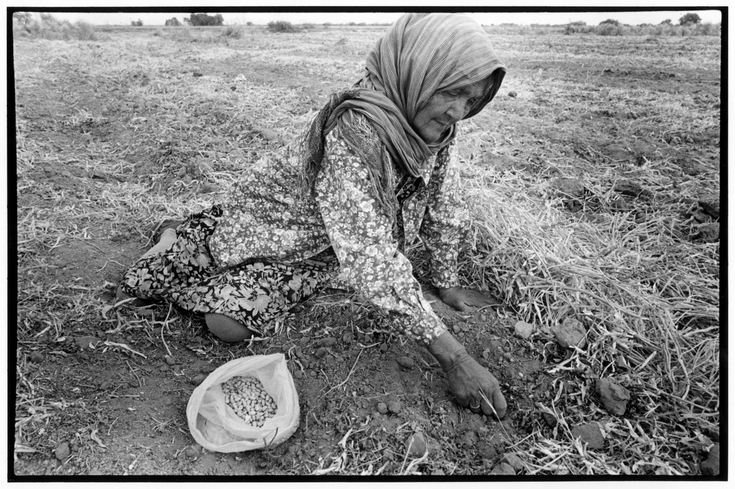

Los Nachuquis, Sonora (3/29/02) A Mayo woman gleans beans from a harvested field. |

DB: In your educational career in the Quinto school, you also got involved with social movements.

My economic situation motivated me to have revolutionary thoughts. At the school, I saw that other students were involved in those movements, and I asked my friends what it was all about. They told me it was necessary to defend the popular classes - the people in the country and the working people - the field workers, the farmworkers. I thought it was a good idea, and I started joining those groups very slowly and cautiously. I wanted to know their fundamental issues, their objectives. I became the treasurer of the student association, in charge of the lunch room and the laundromat. Then I became president. At the beginning I was uncertain. I didn't know where I was going, but I knew it was something very important that I had to do. In 1988-89, we did a lot of good in that institution.

A strike had been lost by the students in 1985. They destroyed the beds, the dormitories, the mattresses- they burned a lot of things. When we arrived, we had to sleep on the floor for the first days, on cardboard with a blanket. There were no dressers. We had to have our clothes in a bag. We felt we'd been left with a lot of problems, and that we had to organize ourselves if anything was going to change.

We started by reorganizing the student association, and brought our problems before the Secretary of Education and Culture. We told the state government that we needed windows, beds, mattress, dressers and services like bathrooms, laundromats, barber shops, and better food. My fellow students would ask how it was possible that they fed the army's horses better than us, who were going to go out and mold the consciousness of young people. We were the ones who were going to combat all ignorance. Once they even fed us rotten beans, so we organized ourselves. We sat in the cafeteria and repeated to each other, "The beans are rotten, the beans are rotten. No one walk out, we must protest!" 500 to 600 hundred of us started throwing our plates in the air. Beans were flying in the air, so were the plates, the bread - as a way to protest for them giving us food in bad condition. They got bad mad at us, but at the same time, they understood. It was a way to pressure them. to make them give us better food, and in fact the food did improve. They gave us windows and mattresses as well.

A representative of the Secretary of Education and Culture, a professor, Alberto Duenas, came to warn us about what we were doing. He talked with us grilleros, the people who were complaining, as we were called back then. He said that if we wanted money, there was some. If we wanted positions in the Secretary of Education, they were there. But if we didn't accept his offer and stop our movement, then we would have to deal with the consequences — that we were going to disappear. We said no. We felt responsible for defending the rights of our 650 fellow students. Thank God we are still alive and talking. I could have become a political prisoner or just another disappeared victim.

I learned that the government was afraid that that once students graduated from school, they would continue fighting and questioning the official parties and the military. Back then there was a clearer political consciousness at the Quinto.

But the response from the government made me think. Knowing that I came from a very humble class and that I was the only hope for my family, I had to calm down. If I didn't, I wouldn't get my diploma. They were depending on me, so that later on I would be able to help them, give them 100 or 200 pesos if they ever had problems — the way I'm doing right now. Perhaps if I had been another person, maybe I wouldn't have been involved in those protests at all. But it was an important period in my life and now I see it in a different perspective. I learned so much from it, and it has helped me in my life and my political participation in the community.

And despite the conditions, El Quinto did give us a very good academic education. The teachers did their best to make sure we'd be well prepared.

|

|

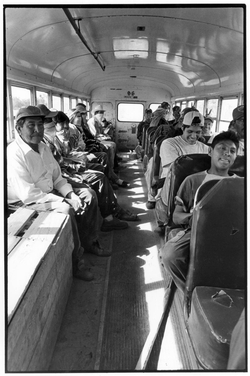

Punta de la Laguna, Sonora (3/30/02) Mayo farm workers on the bus bringing them home from work in the fields. |

DB: So, you graduated as a teacher and you're now working in Trincheras?

I graduated in 1994, with a certificate in primary education, and I went to the state capital in Hermisillo to look for work. They told me, "No, the applications were turned in yesterday. You must wait to be called." I waited for 15 days in Hermocillo, eating beans and tortillas in the street, and ran out of money. I had to return to Navojoa. My friends and I couldn't believe that despite our degree in primary education, we had to go through this situation. It was another sour experience. But we had already assimilated so many bad experiences in the past that one we were able to swallow that one too, very easily.

It took 2 months to get work. Finally they told us that there was an opportunity to teach telesecondaria. We just wanted to work, and we were ready to take anything, even though I had no idea what telesecondaria was. We got our next surprise when we got to the union. Professor Mario Barceloa Abril, the General Secretary of Section 54, said very frankly, that we were not prepared to give telesecondaria classes — we were worthless for that. That was a big blow for us after studying for 7 years.

We organized ourselves and requested an interview with another professor, Enrique Flores. He got really upset. We found out that another group of teachers that had already planned to put their own people into those jobs, and wanted to keep us out. I thought, "How is it possible that the union, the one thing that is supposed to defend the teachers, is suppressing us?"

In the end we were able to get in. All five of us Normalistas were always together and united. But they gave us the furthest positions in the state, which they say are positions of punishment. One of my friends was sent to Mesa Tres Rios, high up in the mountains. Another was sent to a mulatto community on the border between Sonora and Chihuahua. The papers with the names of the locations written on them were thrown on the table and we had to select one. But they were the locations that were the most run down and remote.

DB: What is a telesecondaria?

The telesecondarias are high schools located in rural areas where there are few students. We have schools where there are only 20 students for the whole educational system, and only one teacher teaches them. Those schools are called Unitarias. There are five students in the first year, five students in the second year and the rest are in the last year, and one teacher teaches these kids. There are others with 30 or more students, taught by two teachers. They are called Dos Docentes because there are two teachers. There are others that are called Tres Docentes (three teachers). We have the complete organization in Trincheras, where there are more than 60 students.

In telesecondaria, students are organized in groups of 15 or more. I didn't understand the study plans at first, but now I can see that they are excellent. They feature television programs shown on channel 111, a special education satellite in Mexico. The programs are magnificent, in mathematics, Spanish, history, geography, civics, physical education, and art. They are very complete, and complement what we teachers can give to our students.

DB: So in a course of an hour of class, you utilize the state's program part of the time and then present material in the remaining time?

Yes. For example, I am a teacher of the first year students. In first year the program starts right on the dot at 7 am. From 7:00 am to 7:15, the program highlights mathematics. After the program on math, we turn off the TV because the program then goes on to mathematics two for the second year students. So we turn off the TV and take out our text books. We usually have two books; a book called A Guide to Learning where all of the activities are listed, and another book called Basic Concepts, which contains all of the information. We use those two books on a regular basis. Sometimes activities are not in the Guide to Learning, so we do them in a notebook. We have 15 to 17 minutes of programmed television and we take approximately 34 minutes to explain any doubts, topics and actually do the activities. It takes approximately 58 minutes to an hour. Then the second program comes on, which is Spanish - Spanish 1. That's how the cycle goes until 1 in the afternoon.

|

|

Navojoa, Sonora 3/30/02 Pedro Siari Ozuna was beaten by a landlord, when he attempted to cut branches from a tree for a home altar, part of the Mayo Easter tradition. He was then arrested at the landlord's demand. |

|

|

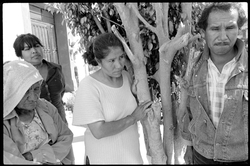

San Ignacio, Sonora 3/30/02 Residents of Rancho Camargo argue with the police who arrested Pedro Siari Ozuna, accusing the authorities of violating their cultural rights as indigenous Mayo people. |

DB: Looking at the community where you grew up, what do you think are the principal problems in the Mayo community?

The principal problem for me is organization. We lack leaders that honestly want to help indigenous groups. We lack people that have good intentions and the desire to truly help people.

Another problem is poverty. A popular saying among Mexicans goes, "Without money, the monkey doesn't dance." So the economic factor plays an important part in the lack of organization, and makes the problem even worse. Leaders come and go, and that is why many Mayos don't trust people who want to help them. They know perfectly well who helps them and who doesn't. It is important that our authorities — municipal, state and federal — support indigenous groups. They need to get out of their cubicles, their offices and go out in the fields and visit them and see their impoverished conditions, that exist right now, in the 21st century.

The attitude of the government has improved. It's a process. I think the break through was marked by uprising in Chiapas. From that point on, I feel like they turned their eyes a little more towards indigenous groups.

DB: Why do you think Chiapas was significant?

Because first of all, they rose with weapons. Authorities here began to think that if the indigenous are like that in Chiapas, then we in Sonora have something bad as well. So the government began looking at indigenous groups differently.

I think hopes also began rising in indigenous communities. There has been more attention paid in the Senate and Congress, in discussions among the governing bodies at state and federal levels. So it has advanced in that sense, but it's a process that is very slow, very slow. The municipal authorities still only visit when they want their votes, but once they reach office, they never come again. I haven't seen the municipal president with the whole committee on a weekend visit a community to see the priority necessities for an indigenous community. I have yet to see it.

DB: Fifty years ago, the government established the ejido system to make it easier for poor people to stay on the land. How is this system functioning?

Since Article 27 of the Constitution was changed, the collectivity of the ejido has been lost. On my families part, when we still had the ejido system it functioned very well. They had good crops and everyone worked.

The ejidos became the work of everyone. Everyone was together, doing collective work. Everyone had their piece of property, but everyone worked their land. The ejido was divided into areas for different crops, and people got paid good money for them. We're talking about 10 to 15 thousand pesos just in one crop. So the system functioned. Farmers had machines and used them.

Now, it has all disappeared. When the changed Article 27 and gave ejidatarios the ability to rent or to sell their properties, the collectivity was lost.

The people who benefitted were the large landholders. Small farmers had to rent their land because their they can't be sustained individually. A farmer alone can't pay for plowing, he can't pay for the water, the seeds, the fertilizer, etc, etc. So he must rent. The ejidatariow we now call the Quejidos because all of them complain. So the situation is drastically different for the ejidos, at least here with the Mayo region. It's a dramatic change. The large landholders tell those who can't read, "No, I rented from you for two crops." They give them a certain amount of money and then never pay them again. Never again. They'll tell people who are illiterate, people who cannot read, that it was really six crops. There was also a large amount of corruption, because after the land was divided, in each section they named a president. But that president often has an agreement with the landowner or with the large capitalists, and he gets paid off while they hurt the field workers.

|

|

|

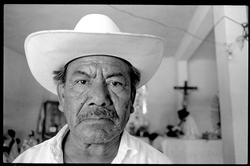

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 4/1/02 Daniel Valenzuela Siari and Clemente Lopez Valenzuela take care of the church in Rancho Camargo, where a priest rarely comes. They organize the pascola fiesta for the town. |

DB: How do the economic conditions of the Mayo community affect the culture? Does it make it more difficult to preserve the culture of the people if they don't have income to sustain the community?

Definitely. It makes it more difficult for the Mayo to actively participate in the indigenous culture, especially the men and the youth. Take a fariseo, for example. For 40 days he's supposed to be on campaign and leave his family, while not receiving any salary. But no one can afford now to be gone for 40 days. So if anything he'll participate for a week. He can't abandon his wife and children for too long, so it makes it more difficult to preserve the culture.

The fiestas lose their spark, and the people don't want to come. So we're losing our traditions.

DB: If the fiestas and other cultural phenomena are sustained by the money gathered from the community, and the economic level of the community is decreasing, there's less and less money to support them then.

Yes that's what it's like. Unfortunately, if we have a poor community, then we're going to have poor events. If we have a stable community, then we're going to have stable events. That's logical. The standard of living in Rancho Camargo is very low, so we're seeing a low level of the culture. There are other communities that have a higher standard of living, and their events show it.

When the cultural links between people in the community are strong, they don't feel the same pressure to migrate to look for work. But if the standard of living is low, many community members are forced to look for work in other places. And the ones that leave here are the young people. Looking for that illusion or that fantasy, they migrate to the cities up north. They have the idea that over there they'll find more wealth or a more dignified life than what we have here in our own community. The young people leave and start working in the border cities, like Nogales and Tijuana. But they return to the fiestas, to continue celebrating the events, so that they don't lose that tradition. It is the need for a job that makes them migrate to other cities, but it's not like they 100% lose their traditions or customs.

We don't have a large number of Mayos that leave the country entirely. Some do, but not in large numbers. It's a minority. The Mayo has a character that I sometimes want to think just tries to get along. Many feel what they earn in Nogales is sufficient. If in a Mayo town I earn 50 pesos per day, and in Nogales I'm earning 80, then that's sufficient. Why do I want to go to the other side? I'm OK here, I can make it with this.

But in terms of education, in terms of getting ahead, we are not at all passive. We are very ambitious. We are ambitious and we will fight until we make our objectives a reality. Half of all the teachers in Sonora are Mayos. Many teachers working up north or in the south come from the Mayo, or Mayo/Yaqui.

|

|

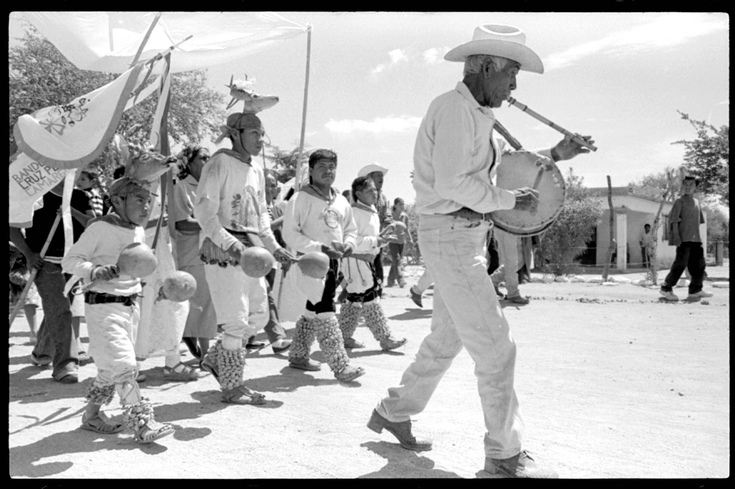

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 4/1/02 The procession at the end of the fiesta on Easter, in which the whole town participates. |

DB: The Mayos don't cross to the other side because they want to maintain their strong cultural ties to their communities of origin?

Perhaps many people feel that travelling for eight hours is enough. If there's a fiesta, we can get their easily to celebrate with the rest of our people. I worked in Nogales, in 1990. People would tell me that on the other side it was very good. I never wanted to go. I don't even have a passport because it hasn't gotten my attention, not even to go shopping or to go on trips. I'd rather go to exotic places in Durango or Michoacan, or Acapulco. I never thought that the other side was the best thing for me. My main desire was to study back then and thank God, I did it. I love my race and my country.

|

|

Rancho Camargo, Sonora 4/1/02 The procession at the end of the fiesta on Easter. |

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-