|

|

Cananea

Three Miners

Moises Espinoza Valenzuela

Jesus Morales Tapia

Genaro Sanchez Camacho

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview With Moises Espinoza Valenzuela

Cananea, Sonora (12/6/01)

DB: Where were you born?

I was born here in Cananea in Buena Vista, Los Campos Mineros. My parents are from the state of Sinaloa and migrated to Cananea when there weren't even roads to get from there to here. My father left then for the United States, and worked in the mines in Arizona. He worked in Superior for many years, and after the war, he got out. He died in Tucson from silicosis.

I entered the mine at 16 years old, in 1937, and I retired in 1980. I worked for 44 years. Then I left to work in other mines in Zacatecas, in Chihuahua and then in the La Maria mine. After that I returned to the company here, where I worked about 9-10 months more. But then they sold the company and I didn't return.

|

|

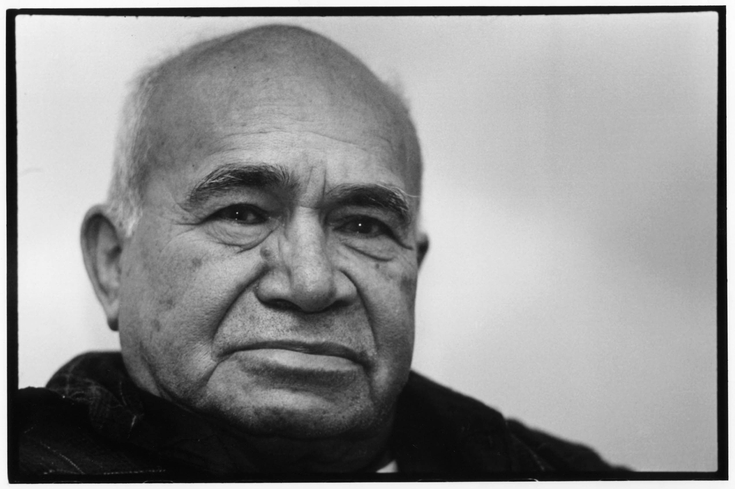

Cananea 12/6/01 Moises Espinoza. |

DB: What work did you do?

I started like everyone else, as an ordinary laborer. But after a while, I felt suffocated, and did different jobs as a result n all mine branches until I became a manager. After that, they promoted me to security, where I lasted there for 30 years. I didn't like it, but they told me to wait until they found an engineer to replace me. They found him 30 years later, so that's how long I was in security.

DB: What did you think about the work in all those years?

Well, the first few years it was difficult. For the ones that started before me, during the years when the mine in Cananea was first operating, the situation was even more difficult. It was a lot of work, with very little pay. As time passed, the situation started to change. The union formed and after that the mine was managed with much more justice. They gave Mexicans what they deserved. During those years, there were workers in the mine from the United States. The Mexican miner did not have access to a manager or a supervisor position. Later, they were given those jobs, after the union. As the years passed, a bridge was opened so that Mexicans could even administer the business.

In 1938, the miners began asking that the union contract include those jobs, so that Mexicans would have access to them. But it wasn't until 1950 when they were allowed to advance into manger and supervisor positions, known as boss divisions. That's when it happened.

I went into the mine on April 22, 1937. It was a very important day for me, which is why I remember the date. At least I could buy other kinds of cigarettes. [laughs]. That's when my career started.

DB: Why did your father decide to work on the other side instead of in Cananea?

He went during the years of the Revolution, looking to improve himself. During those years, Mexico was far behind in terms of union rights. In the United States, miners had a bit more. Another one of his son's was born over there. He was a famous leader, Maclovio Barraza. He was actually the son of another father, but he died, and his mother married my father, who raised him.

We lived for many years together. Maclovio studied over there and began his career in the mines in San Manuel. When the war came in 1942, he came here to Cananea. He was a very young guy, and he grew up and worked here for a long time. Then he returned to the United States and enlisted in the army and went to Korea.

Then he started a career in the union movement, and returned to Cananea during a strike in 1961. He came to see what we needed, because he was a high-ranking official in the leadership in the United States. He saw we had problems here and he came to help us. He tried to bring us supplies and food, but they didn't let it through. They said it was something, if I may say, communist. In reality it really wasn't. But that's the reason they gave for not letting the help for us get through.

After this there was a miners' strike in the United States, and the miners from here, from Cananea, tried to cooperate.

He was as much a union man as I was. I got involved in unions too. Every time he came we'd talk for hours about those topics.

We considered Maclovio completely part of our family. He even asked my father if he could take Espinoza as his last name, but my father didn't want him to. He said that he and his real father were very good friends, and that they had killed him in Superior.

DB: Did you consider working on the other side?

No, because my grandmother was here. She was the one who raised me and she was really worn down, so someone had to stay here. That was the reason why I never went to the United States, besides just visiting.

The company did send me to school there, in San Juan Colorado. I took a special course in mining, but I didn't go to work there. The company paid, so I took advantage of that.

I could see that on both sides of the border they use the same systems. The operations in subterranean areas there are identical to the subterranean areas in Cananea. The workers I saw in the mines in San Juan and Bisbee were Mexicans who worked here and then worked over there. With the experience they got here they went over there.

I only rarely saw any Americans that came over here to work in Cananea. There were a few. We worked together and lived together, but I didn't see them as very satisfied. That was the difference.

The mines I got to know in the United States were not any less dangerous than the ones in Mexico. The subterranean mines have the same risks, so there are rules and practices to minimize accidents. There was less frequency in the accidents there, but this was a time of machismo, and that caused a lot of deaths, to say the least.

DB: Taking risks?

Yes, taking risks that weren't necessary. The workers would do it voluntarily. Perhaps because of the need to earn more money, they took more risks also. And those were the ones you had to hold back- so they wouldn't do it. For example, they had to put gunpowder inside a hole to blast. If they overloaded it, they would be buried and dead with out a doubt. So, to keep them from doing that, one had to have them close by.

The miners from Cananea had the opportunity to work over there. The systems were the same and they mined the same minerals. So as long as they gave them signals, that was sufficient for them to know what to do or how to do it.

DB: Were there any practices or traditions from the union on the other side that they adapted to the union here in Mexico?

Well, they did want to interject the opinions of our union into their union over there, so they tried just being friends. We were all workers in the end. But there were some things they should have fought, for example, silicosis. In the United States, they didn't believe in it, but here in our country, we do. We knew it as an occupational disease and in the United States, it was just seen as common sickness. It wasn't treated as an occupational illness for a long time. When I was in Denver, Colorado, I asked the bosses why that was. And they said that they were sure that the silicosis was an occupational disease, but that business was very powerful in the Senate and Congress, and they weren't going to allow consideration of this. Later, revolutionary people came into the United States Congress and were able to accomplish that. After a while, they were more interested in silicosis than we were here. Funny, but that's how it was.

I think to some degree Mexican miners had an influence on this. Miners in the US had to have been paying attention to what we were finding out. The engineers at the mine school knew perfectly well, but they couldn't do anything. In fact, they had asked for an orientation on silicosis, but they were absolutely not allowed to do this.

|

|

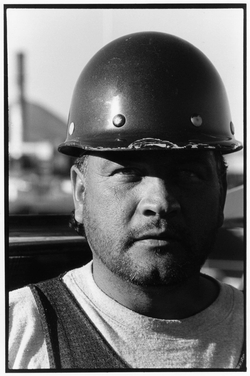

Cananea 12/7/01 A copper miner. |

DB: Are there other ways in which Mexican miners had an influence on the United States, in your opinion?

Well it always seems to be the tendency of the bosses in the United States to hire Mexicans. It's like Mexicans are more willing to take risks. But they pay a lot for it. My brother-in-law died there, in Superior. He had problems with his heart, precisely because of silicosis. He worked for many years in the mines. My father died in Tucson as a consequence of silicosis, but they wouldn't recognize it as an occupational illness. The laws are different.

DB: So then there has been a lot of exchange of people between the mines, regardless of the border?

Yes, of course.. There have been very, very many people who have gone from here in Cananea to Pilares. When I was over there in Bisbee, I met some young men that worked here with me and so the situation was like a celebration. I got to see them again, to get to know them again, to work with them.

DB: Now the difference in wages between Mexico and the United States is very large.

It's much bigger, but it always was big.

DB: Do you have children?

Yes, two men and one woman.

DB: Are the men miners as well?

No. I used to scare them tremendously. I would talk to them and fixed it so that they would be afraid of the mines. One is an attorney and the other is a chemist. My daughter studied accounting and lives in the United States. All of their children are professionals, in the United States and here.

DB: Why didn't you want your children to be miners?

If they sent you to Vietnam, would you have wanted your children to go to Vietnam too? It's dangerous, and I didn't want something dangerous for my children. It's like if you sent your kids to Vietnam, because you went. I always tried to distance them from the mines.

All my family were miners — my father and his father too — but that didn't influence me.

When I'd go to visit them, the little girl was always interested. She was very smart, and she is also a professional now. We'd talk and she'd want to know about being in Mexico from the beginning. I told her some day I'll send you letters telling you things. I started to tell her things in sequence, and the letter's piled up. It was mostly so that she would learn about where everything came from, of how I started.

When I write to her, I write in Spanish and she responds to me in Spanish as well. I always told my daughter to not forget their original language, so in school they'd talk in English and at home she'd talk to them in Spanish.

They feel Mexican and are happy about it. I don't want them to forget the language or become assimilated.

Interview With Jesus Morales Tapia

Cananea, Sonora (12/6/01)

DB: Jesus, when did you start working in the mines?

I entered on the 28th of November in 1950. I was 22 years old. I was born and grew up here and now I've grown old here as well.

DB: In you family, was it expected that a certain age you were going to work in the mines like your father?

When I was young, the most money-making jobs were the mines. There were other jobs, but were badly paid for that period. All of us tried to work for the company. It didn't matter what department. The department that was more dangerous, yet more attractive was the mine. Dangerous because there were many accidents, and very frequently, fatal accidents. But that was the area where more money could be earned because they paid by piece work. Those who were scared would go into other departments. All of us who were not scared entered the mine. At that time, it was shaft mining — subterranean work.

Our pay depended on the job. All of the jobs at the mine depended on how fast we worked — it all depended on production. All of the jobs were paid piecerate, no matter how small they were, so that the extraction of metal would go as fast as possible.

|

|

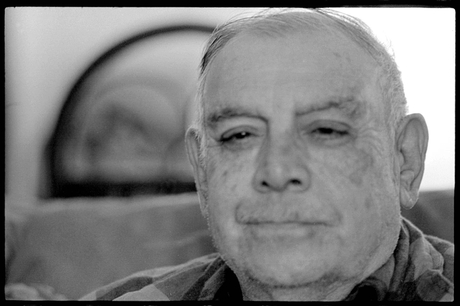

Cananea 12/6/01 Jesus Morales Tapia |

DB: Was this speed the reason for accidents?

No. The work was just dangerous, because of the system they used in the subterranean area. There weren't the advances that exist today. The machinery today is different. In any case, subterranean mines are dangerous, regardless of the machinery.

DB: How many years did you work in the mines?

I worked 2 years in the subterranean mines,. Later, I went into other departments. I worked as a time keeper — we called it the "rayador" — for 11 years. Then they stopped production used subterranean mines, and the operation became open pit, or "cielo abierto." Our jobs ended and I was given the opportunity to go to the concentrator, where I worked another 2 years. In the concentrator, I was called to go to different places, because of the different skills I had. I'd work at the office of the superintendent and at the offices of the time keepers. One day, I was offered a job called public service, measuring water and electricity. At that time, the company distributed potable water and electricity to the city of Cananea. Then I went to a mechanical department as a train dispatcher. I lasted there until 1986, when the company asked me to become a confidential employee. In 1988 I retired.

On my days off I worked in the smelter, because I had to support so many kids who were going to school. I worked anywhere, even on Sundays or on holidays so I could earn a little more money. In 1988, I retired because I could no longer work. My legs gave out. I had an operation on my legs and knees in 1990.

The work supervising wasn't as dangerous, and it was easier. After they started the open pit, we were more out in the open. There was a greater chance to run somewhere in case of an emergency. In the shafts the area was more confined and the mountain is on top of your head always. The falls, the holes — all of it is more dangerous in the shafts. There were natural accidents because of electric shock, metal falling, bodies falling, suffocating — there were many kinds of fatal accidents.

DB: When they changed to open pit production, they began covering all the land around the mine, however.

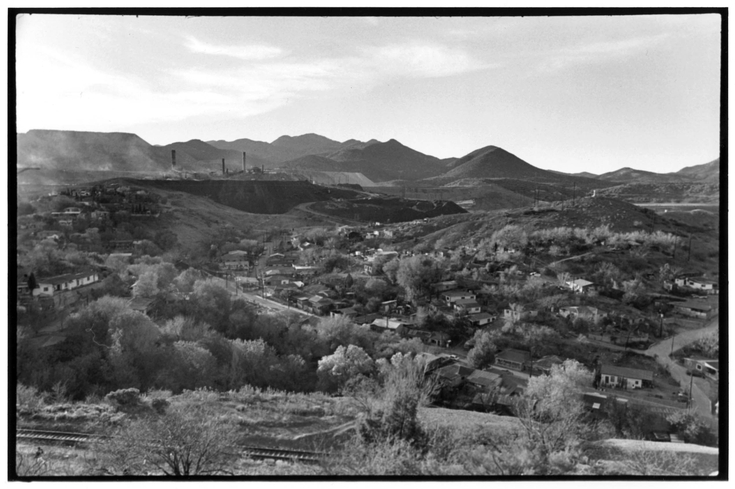

Yes, now you can see large mountains of tailings. It's necessary to strip the mountains to take out the metal. In actuality, the richer ore was already extracted from the inside. Now the open pit produces with very poor minerals. they have to extract ore in large amounts to produce the same amount of metal.

Unfortunately, they're contaminated all of the rural regions of Cananea. When it rains, the water that flows through the soil gets polluted. Sooner or later, the subterranean waters are going to be contaminated. Unfortunately, that's the way it is. I don't believe that the agency or the government is doing anything to prohibit it. It's not like in the United States, where the government makes the companies cover piles of tailings with fertile soil. Not here. Our government, unfortunately has been stupid with the company. They didn't care if they polluted the land. I wish new measures would be taken, but so far in Cananea, there have been no changes.

DB: Is there an ecological group here?

Yes there is one, but there are very few in our country, and they have little effect, because of political problems and because the education of our town about this issue is still too low. There are many factors that make it difficult to have a good ecological group here, but economics and politics are the primary reasons.

DB: Did you ever want to go to work on the other side of the border?

I never wanted to go work to the United States. You're not going to believe it — not even my kids believe it. But I didn't want to go the United States, except to go shopping once in a while — never to work. If the President of the United States himself came to give me permission, I still wouldn't go to the United States. I have lived well in Mexico. I haven't needed anything extraordinary to live. I've never owned a car. I've never envied anybody for having a car. I've never had to have one. I have a nice home, that I made with my own hands. My father-in-law and I built it.

Only one at of all of my brothers lived in the United States. Unfortunately, he was the youngest and the first one to die. He died in the United States. I think life didn't treat him well over there. Earning more didn't do him any good. He had a lot of family, and he had to work very hard just to survive.

|

|

Cananea 12/6/01 |

DB: Today, many of the mines on both sides of the border are owned by the same companies.

It's a worldwide consortium. The owners are the same whether you're talking about mines here or there, or even further away. But the system of capital which is in charge on both sides of the border makes it difficult for workers to get together. The bosses are too tough. They don't give the worker anything. They only give them a portion of what is developed. They're very cheap, very difficult to get money from. They all want to become millionaires- very quickly. It doesn't matter what race they are -- Jewish- Gringos, Mexicans — it doesn't matter. They are people that are looking to quickly gain capital by abusing the worker. I think you see it in the United States as well, where the large corporations don't support the workers.

That's why workers unite. That's why unions exist in Mexico. Unfortunately, over the years the unions have become puppets of the government. Their direction and ideas they had for workers went bad, and the leaders also went bad. They no longer supported the workers. That's what we see today. The union is not what it was 10 or 20 years ago, much less 50 years ago.

DB: When were you elected as a union leader?

I was elected secretary of acts in 1970, for four years. I had the best intentions, and looked for ways to better the union. But there were many difficulties, dictated by the general executive that controlled the union and continues to control it today. The unions on a national level aren't autonomous. The local sections of the unions are autonomous, but they depend on good leaders.

There were many things that couldn't be done. The national leaders had become owners of businesses which contracted to the company, so the workers were manipulated to defend various interests. But that was all done done secretly.

During those years the mine was nationalized, and we struggled to demand compliance with our contract. The boss fought to avoid compliance, and our boss was our own government. We had to fight against a government that was completely clueless about mines. It was a very difficult situation. Then a new era of stupidity came and an American company came in. I won't defend it, but I recognize that working with the Americans was more peaceful than working for the Mexicans. You could possibly accuse me of denying my heritage, but it's not like that. I worked more peacefully with the Americans than with the Mexicans., even though I had my highest earnings when the mine was run by the Mexican government. But it was the government that provoked the miners to strike, and then had to close the mine because of mismanagement. During the American administration, things were handled well, and during the Mexican administration things were handled very poorly.

|

|

|

La Cienega, 12/4/01 The Sonoran desert |

DB: There was also a strike here in 1961, in which miners received support from the other side, in particular from a leader of the US union, Maclovio Barrajas.

After 40 years you forget a lot of things, but that I do remember. After we'd been on strike for a month or two, and we'd sent out commissions to seek help, so that we could continue sustaining our movement, Maclovio Barrajas appeared in Cananea. Maclovio was in the leadership of the miners' union in the United States. He'd married a woman from Cananea, and that gave him ties to us. The family of his wife were miners too.

One day he arrived with a committee of half a dozen miners from the US to give us moral support, and later also economic support. There were Mexicans, or people of Mexican descent, with him, but also Americans. It was welcome help, if only for the fact that once the national leadership of our union knew that the miners in the United States were supporting us, there was more pressure on them to help too. The national leaders of our union have never been any good, even less so now. So those miners were the ones who created the space for us.

Our movement was successful, in part because of the help Maclovio and the US miners gave us. We were very grateful afterwards. I remember that a year later there was a strike among the miners in the United States. It lasted for about a year. With the little that we were earning in that time, we were able to come up with a good amount of dollars to send in help to the United States.

This was in the era we call the epoch of the new plant, which started during the Second World War. The company had to expand its operations, and built a new concentrator and opened up new mines. They invested a lot of money. That was the time in which Maclovio came here to Cananea. Perhaps he came to work. But shortly after he arrived he married a woman from Cananea. They say that he was born here in Cananea too. I'm not sure, but I do know that we were his people.

DB: What was the reason why miners on both sides of the border supported each other during that time?

It's logical. In the first place, we're both communities of miners. Miners support each other because we don't get much help from other communities. Some unions support us for political reasons — teachers, oil workers, and so on. But it's usually more moral support than economic. Actually, the students from the universities have supported us more, and given more direct help to workers. The other unions are usually compromised by their relationship with the government. They don't want to jeopardize that relationship.

Plus, there are family relationships among people on both sides. So there is family affection and fraternal feelings which come into play in a situation like a strike.

But the main reason we support each other is that we all work in the mine. The same kind of work, regardless of which side of the border you're on. We're all miners. When we have problems, there are no barriers, no borders. We all face the same economic situation — we have to look for work in order to survive. Over there they earn dollars, and over here pesos, but the basic problem is the same — work.

The system of work is the same, on both sides of the border. During the time of underground mining, it was the same. Now that it's all open pit, it's still the same. The companies have huge pieces of equipment, on which they need the best operators, and there are lots of workers here in Cananea who know those jobs well. They can work on the other side, and the company knows they'll take good care of the equipment. Someone who's had experience on a job in a mine here, can do that job in the US just as well. The big difference is that miners over there earn twenty times more than we do.

Occasionally, there have been people from Cananea who have worked in mines on the US side. It's not a rare thing. Sometimes people have worked over there as long as ten or fifteen years, and often without any papers. It's only in recent years that the situation has become much more difficult for migrants.

DB: Historically, hasn't there been a strong connection between the Mexican workers in the mines in Arizona and those who work in this country, especially in Cananea?

They were more or less the same people, because the mines in Arizona had a lot of Mexicans who worked in the subterranean mines. They were driven by the same need at the same time. During the 20's and 30's, it wasn't too hard to work in the United States. Miners in Mexico didn't envy others working over there, because you didn't make good money working in the mines in the United States. More recently, when the open pit started, more people left because they began paying better in the United States.

DB: Have there been workers from the other side, Anglos, who have worked in the mine in Cananea?

Not as operators, not since the union was formed in 1936. But there have been Americans here who have worked in the administration, as engineers and technicians.

DB: Is communication important between the miners here in the Mexico and those in the United States?

There's not much relationship during normal times, because our situations aren't the same. The relationship comes about during strikes because the needs of Mexican miners are much greater, because of the economic differences.. During normal times, miners on the other side don't need our help, and we're separated by the barrier of language as well. The leaders of our unions change frequently, and there are a lot of political problems here in Mexico that get in the way of a stronger relationship.

It's difficult to even have good relationships between our own unions here in Mexico. I was the leader of the union and we never had relationships with other unions in our own mining system. Only when there were problems would we look to each other for help. But there usually aren't problems like that. People have too many problems of their own to look for somebody else's.

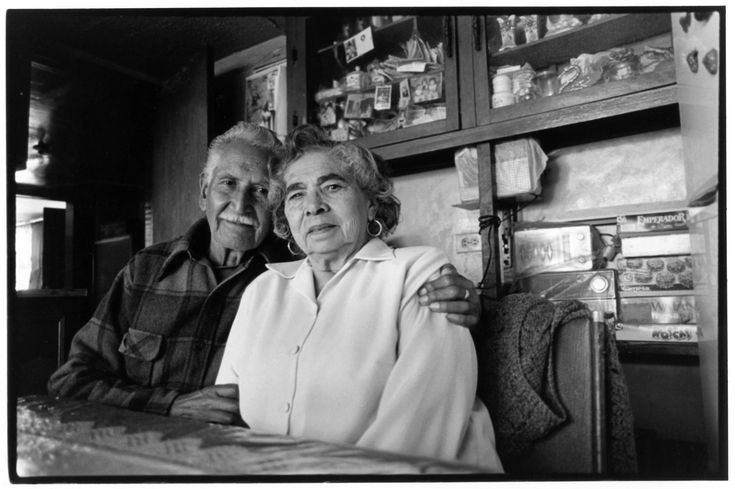

Interview With Genaro Sanchez Camacho

Cananea, Sonora (12/7/01)

DB: Were you born here in Cananea?

No, I was born in San Luis, Arizona. But I was brought here to Cananea when I was really little. I was a few months old. My father worked for a long time here in the mines. He died from silicosis.

I stared working in the open face in 1942 during the war. An American company came to work the copper. And I worked in the mines for the next 45 years. I married my wife in 1944, and we had two children —twins, a man and a woman.

DB: Do they live here in Cananea?

No. My son is a veterinary doctor and lives in El Muncio. My daughter, Trevina, is a teacher at the high school here in Cananea.

DB: How many years ago were you able to buy your home here?

We used to live in Buena Vista. The homes were made out of wood there.

Then the company gave us the option to buy a lot, and loaned us money to build a house. So we have lived in this house since 1976. I retired in 1987. I worked in the office as a time keeper for all of those 45 years.

|

|

Cananea 12/7/01 Genaro Sanchez, timekeeper at the Cananea mine for 42 years, and his wife in the kitchen of their house. |

DB: I want to ask you about what you saw in 1998, when the caravan came from the other side during the strike. Can you describe what happened on the day the caravan arrived?

That caravan was organized because the miners were seeking help during the strike. They didn't have the money to support the movement. They had put aside a certain amount of money, in case of a time when there might be a controversy. But when there's a movement like that, it doesn't last long. The money runs out. So, they have to go out and seek help. They went to the United States, primarily to Arizona, where they were able to get a lot of help. Many organizations came and brought support to Cananea.

On the day of the caravan, we were all there at the union waiting for them to arrive. There were many people waiting for them, and they were very happy because of what they were bringing. Sometimes people would only eat once a day and sometimes they wouldn't even eat. They needed that help a lot.

There were about a thousand people there — a lot of people When the caravan arrived there everyone applauded. Then all of us went into the union and some people spoke. The American's that came could speak Spanish. Among them was Gerardo Acosta, my nephew. He came back to his own country. His mother was even there at the union. She came here from the other side to receive her son here too, and she was very happy. The whole world there was happy.

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-