|

|

Cananea

Help from the North

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Jerry Acosta

Las Vegas NV (12/1/01)

DB: How did you first find out that there was a strike going on at Cananea?

My mother and father were from Cananea, and in my travels I heard there was a strike. Jesus Romo, who has some history with the Farmworkers Union and is an attorney in Tucson, was orchestrating food collection. Unions were participating, but it was basically a community effort.

There was discussion by the labor movement in Tucson about this strike. Some locals were already connected to Cananea, like CWA Local 7928. They are telephone workers, and have always had close contact with the telefonistas in Cananea. They've come across the border to each others' meetings, had dinners together and exchanged ideas about the impact of deregulation in Mexico. So there was already this connection in Tucson, much to my surprise.

|

|

Las Vegas NV 12/1/01 Jerry Acosta |

It seems like Tucson has a lot of people who have come across the border over the years, raised children, and have this connection with Cananea. I was just amazed at how much there is this almost blood connection between the people of Tucson in general, even Anglos, with Cananea. And in Tucson, there's also a close-knit relationship between unions and community organizations. As the Arizona State Director for the AFL-CIO., right away that opened my eyes, and I thought, how can we do more? We wanted to expand the participation by labor as much as we could, and it was easy to generate interest in food collection and get the locals behind this issue

Jesus was brokering the arrangement for us to cross the border with the Cananea mayor at the time. I started meeting with him, and we coordinated efforts on food and clothes, and then raising money. I think they raised close to twenty thousand dollars, and organized four trips with truckloads of food. After our first visit, there were three strikers that would come up to help us organize more food drops.

DB: Were you able to get the support of the AFL-CIO in Washington?

I tried to figure out a way to make this more of an international issue. I contacted the AFL-CIO Solidarity House in Mexico, Tim Beaty, about expanding our participation. He was somewhat skeptical, but he lives in Mexico City and has contacts with those national unions involved. He agreed to meet us in Cananea, on the first food drop. He started having discussions with the national leaders of the miners union there. I think he found the exchange murky at best. There was something that wasn't right, in the sense that those leaders didn't want to make the strike more of an international kind of battle. He wasn't getting that kind of cooperation from the national union, for obvious reasons since we know what happened subsequently. But he was willing to engage them, and meet with us and help us organize on the US side. It was limited, because their national union wasn't ready to raise the bar on this campaign.

DB: So it was pretty obvious that they weren't supporting the strike?

Yes, it was. We tried to be optimistic, and tell them that we were supporting them, but you're right. In the end they were the ones who helped break up the strike. The national union, from my understanding, had a hand in it, in conjunction with the government, who brought in troops. And they stopped us too. We had a huge truck full of food that just sat there and rotted because they weren't cutting any deals with us for us to come across. The miners met us at the border, but I think they knew we weren't able to bring any food. There was no way we were now going to be able to freely come in caravans with truckloads of food.

We wanted to keep doing the caravans going, because we felt that if they were going to win the strike it was because they were going to be able to last one day longer, and a little bit more food could help them do that. But he Mexican Border Police wouldn't let the truck pass, and all of a sudden, the local pulled back from us. Something was going on, and I don't know the specifics, but the national union came in and took over. And then the relationship kind of dried up, even though there were three workers who were coming across the border, talking and helping us raise money and food. They lost their jobs in the end, and subsequently thought that their lives might be better here.

DB: Tell me a little bit about your parents, and their history in Cananea. You yourself were born on th US side, right?

I was born in Compton, California, or as my brother says, Compton Lakes (laughs), but both of my parents are from Cananea. My mom was a school teacher theere, and my father was a panadero, a baker. My mom was born in a little town called Buena Vista and I think my dad was born somewhere in Cananea close to Ronquillo. As very young people, they were married and eventually came over here with the help of my step-grandfather. He had married my dad's mom in Cananea and brought her to the US. Then my grandmother and my step-grandfather worked on getting my dad's and mom's papers and then brought them over.

But they were from Cananea, and all of their families are still there. My mom's got two brothers and eight half brothers — the whole Sanchez family, including Genaro. My dad's family are the Hererras, which is a big family also. As a child, we would go back there, and I grew up with this knowledge of what Cananea was and of the mine. I lost an uncle in the mine — there was a tragic accident and he was killed. So, with these roots in Cananea, naturally I perked up right away when I heard there was a strike. I knew how the whole economy goes to shit immediately when anything goes wrong with that mine or when it's shut down.

DB: When you were growing up, what did your parents tell you about Cananea? What did they say about its history and the family's connection with the mine?

As a kid, you just understood the magnitude of the mine and its relationship to the people. I didn't get any great historical explanation, but as a child, I realized real quick that the mine was everything for everybody in that town. At my grandmother's house in Elejillo, which is just outside of Cananea, you could always see the smokestack. Even as a kid, I knew what the mine represented to Cananea and the prosperity it brought. The people had medical benefits, they had good jobs — it was a prosperous town.

My grandmother, Shalela Martinez used to do what they call the fayuquera. She used to go across the border and buy shirts and cakes and then come and sell them. People always used to owe her money. There were days she'd make rounds and take orders from people, and she'd go across the border, purchase American goods, because you know they loved American goods, and then she'd come and then deliver them. If people didn't have the money, they'd give her part of what they owed. Every weekend she'd make the rounds and get new orders, and that's why they called the fayuqua, I guess. As a child I remember going from house to house, and my first experience of Mexican coffee. I remember I was trembling, because I don't care how much milk you put in it, they make this stuff fresh from the coffee bean. Everywhere you go they sit you down and you have cafŽ no matter how old you are. I was only nine or ten years old.

People in Cananea had money because even if you didn't work for the mine you did something, you sold tacos or had some business that was connected to the people who worked at the mine. People had money because the mine was prosperous.

There was this love of our family that was there. After we moved, we really don't have any close relatives in Compton. And so the connection with Cananea was always the love of my grandmother and the love of my uncles and my dad's family. We knew that the connection to Cananea also represented that kind of close-knit love that we didn't have in Los Angeles. We'd go back and forth, and as we got older, us kids would go and stay with my grandmother. My sister was her favorite.

I travel a lot, and sometimes, when I'm in LA, I will go and stay with my mom in Compton. With my work sometimes I'm out late, and she sleeps in the living room with the television on. So I'll be very quiet. She still leaves the door open — in the city of Compton! But everybody knows her. So I'll sneak in and go into the bedroom and sleep. Sometimes I'll have to get up real early, so very quietly, I'll take a shower and leave at five or six,. So I did this this one night. My mom must have seen the bed, and known that I'd spent the night. But my sister called her, and asked, "Mom, is Jerry over?" My mom, she told her, "You know, I think he was here last night, because my grandmother Shanela came to me in a dream and said she went to the house and saw me laying there, and said ÔOh my God, he looks just like your dad!'" (laughs)

|

|

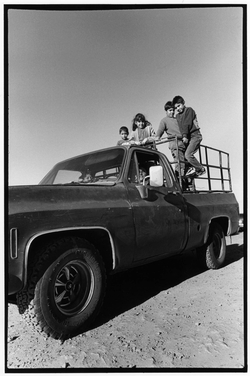

Cananea 12/7/01 A family waits in the mine workers' parking lot for a miner to get off work. |

DB: Did the connnection to Cananea become harder to maintain over the years?

When I was very young, only 22, I became a trustee for my union at the Southern California Gas Company. By then I was already a father, and I had a wife and it was much more difficult for me to go back. Then I was elected president of the gas workers local when I was twenty eight. I would go back for funerals, but it became that kind of thing. Then after several years, I went to work for the national Utility Workers Union. I would visit Arizona when I was trying to organize workers at Southwest Gas in Bisbee and Douglas, and there were times I'd go across. I'd sneak across and try to visit my uncle or see someone and then come back.

Then I left the Utility Workers and took this job at the AFL-CIO a little after John Sweeney was elected president. As the new state director of the AFL-CIO, I would go to Tucson, so I would sneak across more frequently and see my uncle. After the strike I got into the habit of taking food over there, because afterwards the economy was horrible — just delivering canned goods to my family, or dropping off clothes. I'd grab what my sisters had collected, then go to Costco and buy canned stuff like hams. We used to do that when we were kids, and I remember when we were little, every time we'd go to Mexico we'd take these boxes of clothes.

DB: What was it like going to Cananea during the strike?

I'll never forget it. I was driving my van, and when we came into the city, I saw hundreds and hundreds of people waiting for us. And I thought to myself "Oh, my God, we don't have enough food! (laughts) We gotta come back! We've gotta organize more!" I was overwhelmed. My cousin, Fausto, who they used to call el gavino banera, is a singer. They called him el gavino because he was always walking around singing while he was working. He had a deep voice, and as kids he lived with my grandmother Nejido. So he pulls up next to my van in his truck, and I haven't seen him since we got married. We go into this school with our load of food and all these people are there — my cousins and old neighbors — and the street is just full of hundreds and hundreds of people. We're like celebrities to them. And one of the first people waiting for me was my mom.

I had told her what was going down there. So there she was with my uncle Genaro. They took us into this hall, where they had this huge union meeting. My Spanish is horrible by anybody's standards — you know, without the practice — but we spoke. Everybody took a chance and said something to the crowd. I don't know how to say it, but they were very happy we were there, and we could see the solidarity of the workers and their leaders, how they were going to stay together. They took us out to dinner, as best they could, struggling with the strike. It was one of the most momentous things that ever happened in my life.

Right after that, we started organizing. The Teamsters started raising money at local bars where they'd have a beer. We had canned food drives, and connected with local food banks. That was difficult because they're not supposed to take food across the border. The food banks are for locals. But I'm on the executive board of a community service agency in Phoenix, and I made a plea for money and food, and they responded.

DB: Were miners unions in the US involved in raising the money and food?

Yes, but it cut across that. There were machinists who had family connections in Cananea, and Teamsters and other kinds of workers too. It was an issue for miners on this side of the border, but I think Cananea is something special to Tucson in general. I didn't understand that until the strike, but it cut across organized labor and community organizations and religious people too. The interest was huge.

DB: What is this connection between Cananea and Tucson? Why are people in Tucson aware that Cananea exists — why is it important to them?

Lots of people have cousins who were born in Cananea but now live in Tucson. People from Cananea shop in Tucson. Everybody has family there or some connection or some history that involves the migration of people from Cananea to Tucson.

The miners in southern Arizona obviously have a connection. Some of the people that worked in the mines in Mexico have came across and worked in mines in Southern Arizona. There is a rich culture and history of miners and the struggles they've gone through in Arizona, including some very horrible history — the Phelps-Dodge strike and so on. Miners have a close-knit community on this side of the border, and the association with Cananea is part of that vital connection.

There are families who work in mines on both sides of the border. Unfortunately, that's declining now. Mining in the US is a pretty depressed industry at the moment. But in the family of miners, a strike is a strike and people think, "we gotta hang together." There's a special kind of solidarity between miners across the border.

The strike also started a relationship between labor and the community in Tucson, that became very strong bond between me and the people at Derechos Humanos, the immigrant rights organization there. Following their lead I became involved in the movement to stop the deaths among workers coming across the border. People were dying every day in the summer, and that became a huge issue, and I was able to participate. So I think unfortunately we weren't able to expand our endeavors in Mexico, but the relationship between the AFL-CIO and community people in Tucson people was very productive and became very close.

I really don't see any difference between organizations like Derechos Humanos and the labor movement. We're working now to get building trades to start organizing the Latino workers, to look at them as potential members. In Arizona sixty percent of the workers in commercial construction are Latino — Mexicanos, mostly undocumented. Sometimes the labor movement isn't connected with that community, and Derechos Humanos is a resource. Derechos Humanos, they're just a breath of fresh air, and they keep people like me anchored about what's real. If I can carve out any time for their issues, that's great for me — it's good for my soul.

|

|

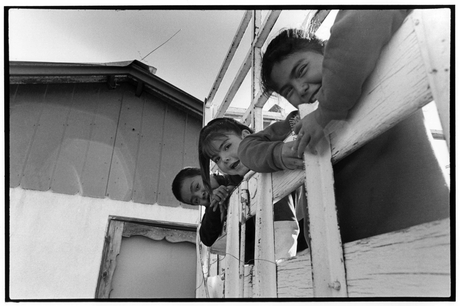

Cananea 12/7/01 Miners' children wait for their fathers to come home from work in the Fracc. Napoleon Gomez Sada, a miners' neighborhood. |

DB: There are strikes and various kinds of organizing efforts in the maquiladoras along the border pretty much all the time. Is Cananea an example of the kind of support US unions could provide for them?

Maquilas are shutting down at an incredible rate right now, because of the recession in the US, so it's obvious we're connected. The number one employer in Mexico is General Motors, and the second one is GE. It gives you some idea of why we should be engaged and have a higher level of contact. We get lost in all the work and all the things that are broken on this side of the border, but that's what we need.

I think that this thing that I found, this closeness between Cananea and Tucson, I'm sure exists between other cities too. All along this border there are really strong connections — family, cultural, and historical. From a work perspective, there are relationships with workers on the other side in the same industry or sector. I think the bond is strong and that if we were a little focused we could develop it much more. In the AFL-CIO we could do a better job of reaching across, especially with when it's in our own self-interest to do that, to develop those bonds and be engaged on a higher level.

DB: Do you think that Mexican culture is influencing the way workers do things on this side of the border and changing the ways that unions do things as well?

I think there's this way of thinking that "I'm a hard worker, but you know what? I've had enough." With this, people were able to use that whatever they brought from the other side of the border to take a stand. Think of the janitors' strike in Los Angeles. Nobody has cars — they take the bus at four, five, six in the morning, and they're marching all day, and they had kids. They didn't have babysitters, eo they'd bring their kids to the strike. They were hungry, and we'd try to feed people as much as we could on the strike line. Then they'd catch the bus late at night. Sometimes I'd give people a ride home, and I'd drop people off all over Los Angeles — East LA, Bell, Ramparts — all over. Then the next morning they were at it again, manning the picket lines and hanging together. So yes, I think it didn't just come out of nowhere. I think that spirit comes from the other side of the border.

I think, like my father, they make a determination that "this is it. I'm going to take this position." They're more ready to take risks. It seemed like my father was always on strike, ready for those consequences if we were to have a better life. As a child I saw he had the machinists emblem on his lunch pail and on his pocket and on his little pencils, and I would ask him what they were. He'd say, "that's for a better life for you."

Some of my uncles, the Herreras, were very well to do and worked at the Smith Tool Company. My dad was a welder, and he'd weld drilling sleeves and drilling bits for large oil companies. There was an organizing campaign, and my dad was not an organizer — he barely spoke English — but he was one of the leaders. My uncle was the superintendent of this huge plant, and a couple other uncles worked there. When they went on strike my dad was the only one in the family who went out. He'd been drinking one day, and he told me to get in the car — he was a man of very few words. We went down to the railroad tracks, and he collected the best rocks he could find. He had a bagful of them, and there was a parking lot where all the cars of all the scabs were parked. So my dad parked in a field behind it, in broad daylight.

We weren't hiding. We sat there, and he tossed those rocks, breaking windows in the parking lot. I was a kid, and nervous of cops, but he didn't care. He just sat there, and I guess he felt better when he depleted his stock of rocks, so we got in the car and we went home. I remember going to union meetings with him, so it was quite natural for me when I went to work right away to look for the union organizers.

There was just this absolute solidarity that he had. I guess Mexicanos from that side of the border bring a level of solidarity that when called upon is significant. He was a Mexicano, and after a certain point they get fed up, and they can be tough. They're the greatest people in the world, the hardest working people in the world, but, you know, when disturbed and when fucked with, they shut down on you!

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-