|

|

Cananea

Miners' Union Officer

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Gabriel Parra Cortez

Cananea, Sonora (12/7/01)

DB: Were you born here in Cananea?

Yes, on the 26th of September, 1958. I was born here in the Obrera Clinic. The Obrera Clinic was part of the union, but it is now closed.

I started work in the mine on the 21st of July in 1975, and I've worked there for 25 years. I've always been an operator. I first started as a stamper on the open face. Then I became a bus operator. Now I'm a shovel operator. Well, since I started working the work has become more modernized. For us workers, this was significant. We felt better about our work. We were working with the latest technology. The mines here in Cananea became well known because of that. And working with large machinery, we forgot about the work of our ancestors.

|

|

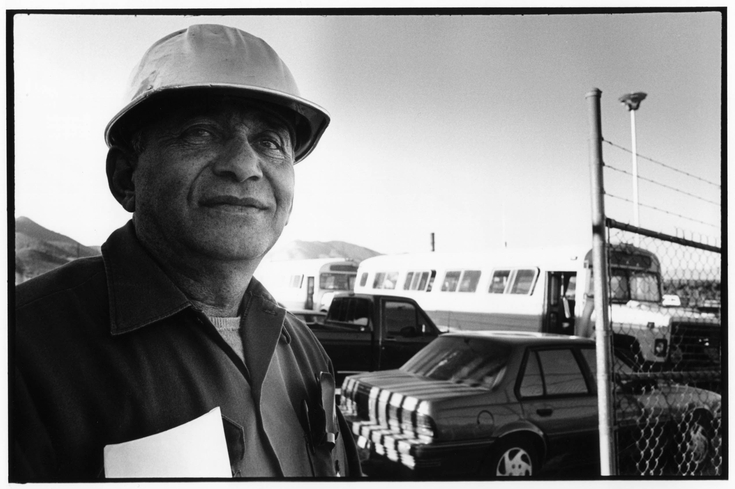

Cananea 12/7/01 Gabriel Parra, an activist in Seccion 65 of the Mexican Miners Union, in the Fracc. Napoleon Gomez Sada, a miners' neighborhood named after the former national head of the union. |

DB: Did your parents work in this mine?

My father also worked here for 35 years. My grandfather, Ramon Cortez, also worked as a miner. Genaro Sanchez, who's also part of my family, worked as a miner. When I was young, Genaro was the one that gave us our time card so that we could work. He was very strict, that Genaro. One couldn't get to work late. We need that discipline again now.

My grandfather on the maternal side was from Sinaloa, and on my dad's side, from El Tigre, Sonora. It's a well known mine, next to Nacozari. They gave my dad a diploma for working here so many years.

DB: When did you get involved with the union?

In 1989 I was fired for not wanting to work because of unsafe conditions. The administration of the company got mad at me and dismissed me. We stopped working for a month — illegally. During that time I was the union representative in my area of work. So, when I was dismissed, my coworkers supported me. We went for a month without work, but we stopped the mine. The concentrator and the smelter continued to work and at a union assembly the workers there agreed to give us a day of salary so that they could help us while we continued the movement.

DB: So, the mine was stopped for only one worker?

For a month. We stopped one month because they dismissed me.

DB: Why did people consider the job of an individual important?

Because I was a union representative and that was the reason why they fired me — because I tried to protect the workers' rights.

During that time there were rumors going around that we were cry babies and lazy here in Cananea. So the business started to tell the union that they couldn't tolerate us because we were stopping work every second. Effectively, if one of the workers were fired from work, we considered it incorrect because it violated our contract. And the truth is that we did do a lot of stoppages, or paros, during that time.

From the beginning the membership of the union supported us, so the union nationally couldn't do much else but support the workers' position. We went back after a month, after our national union's leader, Napoleon Gomez Sada, intervened and the company reinstated me. The government's secretary of labor, Emelio Gomez-Vivez came twice.

They didn't pay us salaries for wages we lost. They only reinstated us and we returned to work. Two months later, on the 20th of August of 1989, the Mexican army came and kicked all of us out. They expelled us from the mine. Here in Cananea, it's called the "Green Sunday". They said that here in Cananea we had a lot of guns and that we were rebellious workers. They sent five thousand men from the army to get us out. They arrived at 5 am and they started expelling our co-workers on the night shift. The ones who were going to replace them were denied entry.

The mine closed. The army was in charge of everything, including the smelter oven. The workers there opposed the army taking over, because if the fire running the converters was extinguished, there would be problems. But the army did not permit them to remain at work. They only let us gather our belongings, and told us to abandon our jobs, and stay inside of the green line made by the army. They made us walk in between the lines. Nobody was able to stay at work.

It all lasted about 3 months. During that time, we all stayed here without work. A commission of 30 workers was formed to go to Mexico City and here in Cananea other commissions were formed, including a strike committee. We went to different states of the republic and some co-workers went to the United States.

We had lots of support from the United States and from here in Mexico. Thanks to them, we were able to go back to work. But my impression was that the governments of both countries didn't want us to relate to each other, and try to resolve the issues as quickly as possible.

DB: Did you speak specifically to other mine workers?

We accepted the help of whoever came — politicians, national, foreign. People from the United States came and supported us with food supplies and clothes. Many organizations came, and there were other miners within those organizations. I was responsible for coordinating the strike in the states of Sinaloa and Sonora, so I was always outside. When I'd come home, I'd see what was happening. Nobody had work. During that time the republic's President was Carlos Salinas de Gortari and he ordered the municipal president to pave the roads with cement. In that way, the mineworkers could work and sustain themselves. In reality the work done to the pavements was done to the areas that were already paved but were badly deteriorate. They put new pavement on.

When the company declared bankruptcy the movement stopped, and we started working again with certain modifications. La Nacional Financeria Azucarera (The National Sugar Company) became responsible for the mine. They closed the open face and we started to have problems with exhaust. Then the Industrial Minera de Mexico bought the mine. The president of that company was Jorge Larrea. Right away there were problems because the union contract was modified to eliminate what the company said were barriers to productivity. There were also problems interpreting the contract.

Here in Mexico there was a campaign against the workers of Cananea. They said that we were lazy and crybabies, things that were not true.

DB: Who was responsible for campaigning against you?

The Mexican government itself. Politicians began to pay people in the press to say these negative things, and the media publicizes what is asked to. The Sunday Supplement to the Imparcial released photographs, and said that we lived in first class homes, that we earned a lot of money and that we didn't do anything at work. They said that we were the cause of the bankruptcy, because of the work stoppages.

|

|

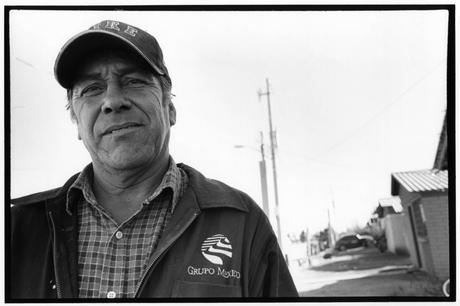

Cananea 12/7/01 Mauro Lopez has been a mechanic on heavy equipment in the Cananea mine for 22 years. He wears a jacket with the logo of the mine's private owner, Grupo Mexico. |

DB: I understand that as the years passed, the company started cutting back the number of mine workers.

That is true. The company had a lot of funding problems. There was a cut of 100-110 people that opted to retire voluntarily. They were paid off and left. One way or another, the workforce diminished a lot. Then in 1998 there was the massive cut, when 719 workers were cut back. Now we are only 1,200 workers and in 1989, we were 2,200 - 2,300 workers.

DB: How did the union respond to this?

In 1998 the company said they no longer wanted to operate the dam and city waterworks, which require around 60-80 workers. Some thought we should organize an illegal general work stoppage, like we did in1989. Others argued that those 60-80 workers should stop work, and that the rest of us, who were over 2000 at the time, could have helped them to maintain themselves for a while. If we couldn't, then we would have had the option of negotiating with the company, and while 60 workers would be lost, it wouldn't have been 8-900. But there were approximately 800 miners left without a job in 1998.

Within the union there are internal currents. The majority supported the general secretary, and another current supported the company. The workers wanted to stop work because they're very brave, so we voted for the general stoppage on the 19th of November, 1998. I saved the general secretary by making a speech in favor of it myself. On the 20th of November the Mexican Revolution is celebrated here, so there was a parade. They invited all of us to join to protest against the cuts and all of us joined. It created quite an impression because there were a lot of workers, lined up six by six. The contingent that the workers created was much larger than the one the schools did.

But we all suffered because it was a failure. Up until then, every time we had a stoppage, the company would ask us to go back to work and talk. This time it was backwards. We wanted to go to work and talk to them and the company administration said no. I sat with the Secretary of Labor in Mexico City and the national head of our union, Napoleon Gomez-Sada. Napoleon was proposing that all of us would go back to our work, but the company started to talk about all of the disagreements they had with the union. They said that we had already stopped, and that there were some things we had to talk about. Once all of them were resolved we could return to work. That's how it was and it cost us 800 workers.

DB: So the company started by asking for a cut of 60 workers, but once this stoppage happened, the company demanded more massive cuts?

Yes, their demands grew, and they began saying they were going to close the smelter. Close to 400 workers worked there, and the company said they had to close it due to pollution problems. First they closed a smelter in Douglas, Arizona. Then they closed Cananea smelter. They were very old ones that polluted the environment. Here in Cananea, in 1989, when we went back to work, the government promised that they were going to invest in the smelter and modernize it. But all of the remodeling was done in Esqueda, next to the mine in Nacozari, and not in Cananea. They made a super modern smelter that is processing all the metal of Cananea and other Mexican copper mines.

DB: Once the work stoppage began in 1998, what happened?

After we all stopped work, a commission was formed. We went to talk in Mexico City, and we went back and forth a few times. The Secretary of Labor during that time told me to go back and convince my co-workers to return to work. But when we returned we were unable to convince the people. Then the company administrator said they wanted to just end all the problems, and they ended them by closing the smelter, the water system and other cuts.

In 1998 the company no longer belonged to the government. It was owned by private capital and Napoleon Gomez Sada's power had diminished. He wasn't able to do anything to change the minds of the private owners. We weren't able to fix anything. We had to return with the shame of losing 800 jobs, and not being able to solve any of the other problems that had caused the stoppage, not even lost wages for the time we were out of work or anything. It was very painful.

The Secretary of Labor came here to Cananea. A state deputy came with a representative of the national executive committee of the union, and met with the local committee here in Cananea. We spoke to the workers. The meeting was very difficult. We had been out of work a long time building our movement, but it got out of hand and cost us 800 people. The generous help that we received from all of the people wasn't enough. We spent a very sad Christmas with our families without the traditional dinner celebrated everywhere. We returned to work with 800 workers less and with the same conditions.

We were able to salvage the same contract. There were occasions when the workers no longer wanted to continue the stoppage, but no one that had the courage to say that stopping it was necessary. I was the one who made that proposal. That same day, I was scared that I might get beaten at the union for saying that it was necessary to go back to work. No one in the leadership of the union wanted to make that proposal, and in the meeting there were others who said we should continue the stoppage. I stepped up to tell them that they had to submit the agreement to a vote. The chair of the meeting asked the people if we should lift the strike and to everyone's surprise, it was agreed. All of us went back to work, minus the 800 that didn't.

|

|

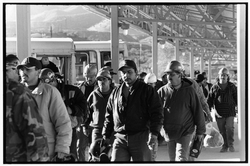

Cananea 12/7/01 Copper miners getting off work. |

|

|

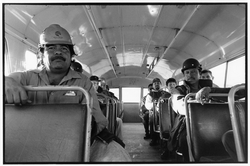

Cananea 12/7/01 Copper miners at the end of their shift on the bus which takes them into town. |

DB: How was the work of organizing the support from the North organized?

We named a commission. since we already had contacts with different organizations and unions of the United States when they helped us with the strike in 1989. During that strike the army had come in, and this news had a large impact in many areas, which helped us in Cananea. So, we looked into our files and got their addresses and phone numbers and began to communicate. It was spontaneous, including the help from Arizona. We sent a commission over there to hang out and organize the support.

DB: What has happened since the movement ended?

Well, we continue to work, but problems have arisen. In 1999, on the 22nd of December, Napoleon Gomez-Sada became ill. He named his son, Napoleon Gomez Urrutia, to inherit the union. I don't agree with the idea that his son should inherit the position, so I was punished. They took away my position. He wasn't able to take away my job because that same year the Supreme Court took away the ability of unions to use the exclusion clause to remove people from their jobs. Before, if they had considered me a back stabber, they could have even taken my job. But, now, Thank God, that law no longer exists in Mexico. Now, if I don't want to be part of the union, then I don't have to and they can't take away my job.

They're punishing me for 3 years. And now the Mexican government has recognized the son as the leader of the union. President Fox is failing to keep the promise he made in his campaign, that no one could be above the law, that corruption was going to end, and that these things weren't going to continue. That's why people changed political parties in Mexico, because they're tired of this, and we don't want to just repeat the same the same things we've seen before. Fox is going to shout to the four winds in different countries that the PRI [Mexico's old ruling party, which he defeated] was the worst that ever existed and that the PRI was responsible for all of the bad things that have happened to Mexico. It is true, but he's the same.

The son was never a miner, and we can prove he never worked for the same wages we earn for 8 hours. The only proof he has is that he has the same blood that his father had. We've returned to an era of monarchy, where the king gives his throne to the prince. They have punished us and beat our co-workers in Nacozari. Others were recently beaten in Monclova and in Lazaro Cardenas, Michoacan.

DB: Why do you think the government is doing this?

Everyone in the world knows that miners yell more than anyone, perhaps because of the difficulty in work, and the ones who yell the loudest are the ones who work in substandard mines. In Cananea we work in modern mines, but we still have a tradition of struggle. We know how to organize a strike legally, but by installing Gomez Urrutia, they took away our ability to do that. We know that we can't make illegal strikes the way we did before. And we don't know how to solve our problems politically anymore. So now there's no way we can win. Gomez Urrutia was supposed to notify the employers that we wanted to bargain wage increases this year, and he failed to do it. So we're left without a raise or the means to get one.

DB: Do you have friends or family that have gone to the United States to work as miners?

Yes, my uncle Manuel Parra, worked in the San Manuel mines, and my cousins, too. But not anymore. My uncle retired and my cousins decided not to work in the mines and do other things.

Many people from Cananea migrate, especially to Tucson — people able to get their citizenship and work over there. There they pay them like they should be paid. Sometimes we talk among ourselves and say that so and so works in so and so mine and is doing well and earns so many dollars an hour. We open our eyes really wide. [laughs].

DB: Is there an influence on the Mexican unions from the unions in the United States? Or the other way around- that the Mexican unions influence the North American unions?

Vicente Fox and especially, Carlos Abascal Carranza speak about a new labor culture. The have us blindfolded because we don't know what the labor culture will be. We're accustomed here to the idea that every year, for example, the government says employers will give 10% raises to the miners sector, to the electrician's sector they're going to give a 15% raise, and so on. We don't know if we'll even get these automatic raises every year in the same manner, or if they're going to have another system like what we imagine it's like in the United States. Maybe they'll raise wages differently for different jobs.

Here in Cananea in 1995, we negotiated an agreement in which our raises were tied to an increase in productivity. We were the first in Mexico to do this. We have not been able to adequately resolve the way they calculate this, however, because feel that the company benefited from the increased production while we didn't benefit with higher wages. We've had a year and a half without a bonus, and without the 10.5% that we were going to get this year. We, the miners' of Cananea, are hurting, and mining work is not as attractive as it used it used to be. It used to be that to work in the mines, was like a profession. We lived well, but we also worked well. The company is going through a crisis because of the low price of copper. They think with new machinery they should be getting more, but they don't have it. We put our soul into it. We make an effort. But we can only do what the machines can do.

|

|

Cananea 12/7/01 A copper miner |

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-