|

|

Cananea

A Striker's Story

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Javier Cañizares

San Francisco CA (3/15/99)

DB: Why did miners in Cananea go on strike in 1998?

The workers went on strike because of the violations of the contract, the closure of departments, and the massive layoffs of workers.

DB: What happened during the strike, and how did it end?

When the strike started, we began negotiations between the Secretary of Labor and the national leadership of our union. They said that for Cananea to return to a peaceful situation, we would have to accept the elimination of jobs. When they brought us this agreement, we weren't willing to accept it. We began to mobilize ourselves and organize large demonstrations throughout the whole state, and even nationally. We wanted the solidarity of many other organizations. That's how we were able to sustain our movement over the course of three months.

|

|

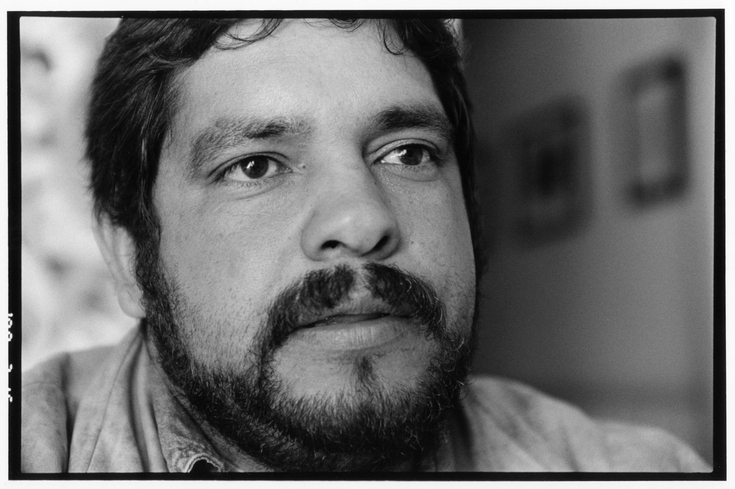

San Francisco, California 3/25/99 Javier Cañizares, an activist in Seccion 65 of the Mexican Miners Union, was a leader of the Cananea strike in 1998. He came to the US to seek support from US workers and unions for the strikers. He was blacklisted at the end of the strike. |

Some of the strikers went all across the United States looking for support. We got a lot of moral support, and economic support also.

On the ninth of February, in the absence of our union representatives, the governor of Sonora and the Ministers of Labor and the Interior intervened, and reached an agreement. It said that it was necessary to close four departments and lay off 1000 workers. They said that the voluntary elimination of 1000 jobs didn't constitute a massive layoff. But we, the workers, understood that these were forcible terminations.

Eliminating 1000 jobs in a town like Cananea means turning it into a ghost town, given that the only source of jobs for the town's 35,000 residents is the mine.

DB: So what happened at the end of the strike? What did the workers do?

The authorities said there was nothing we could do about the elimination of jobs. So the workers decided to end the strike and go back to work.

The surprise for us was that on having decided to go back to work, the company posted lists of people who would be going back. This caused a lot of turmoil among the people, since the lists didn't include people who were very active in the strike, in addition to the people from the closed departments. So we had a big meeting to discuss what had happened. And in the meeting we decided to go in and occupy the mine. This means that each person was supposed to go back and occupy their job in their department.

The day after we'd gone into the mine, there was a big movilization of the army and all the police forces in the state of Sonora. So the mayor of Cananea, accompanied by the general secretary of the union, went into the mine and asked the workers there to leave, that they were running the risk of repression.

To this day many people who were active in one way or another haven't been permitted to go back. They're still out of work. The company says there's no way they're going to let them come back. These are 120 workers who were working in departments that weren't closed. The fact that they weren't fighting for their own jobs, but for the jobs of others, made the company afraid. That's why they don't want them.

The leaders of our local union went to the company, and said that there shouldn't have been any problem with these people, since their departments hadn't been shut down. The company responded that they didn't want people who weren't in agreement with the changes. They said they only wanted people who would go along with their decisions.

DB: The Cananea mine is an old one, and was nationalized from the 1970s to the 1990s, and then sold to private owners. What effect did that have on the workers? Did it have anything to do with the causes of the strike?

When the government begins to talk about the privatization of a business, it talks in terms of higher salaries and better benefits that will be possible under the new owners. But in Cananea, our experience was just the opposite. After the mine was privatized, we began losing our benefits bit by bit. The company didn't respect our union contract, or even our human rights as workers.

DB: When the mine was sold to Grupo Mexico in 1991, how many miners worked in the Cananea mine?

When they privatized the mine, there were about 3500 workers. Today there are 2070. The company brought in people from Veracruz, Guerrero and Michoacan, to take jobs as they became vacant. But they gave those workers lower salaries and benefits, and said they weren't covered by the union contract. They were brought in as temporary workers, on 28-day contracts. So the work itself didn't disappear, but the people who did the jobs changed, and weren't under the contract anymore.

Under Mexican law, workers don't acquire seniority and become permanent and eligible for benefits under a union contract until they've worked 30 days. So with 28-day contracts, these workers were never permanent. Grupo Mexico has an affiliated company, called Constructora Mexico. This company was in charge of bringing in these other workers.

DB: What happened to the people who lost their jobs, whether at the end of the strike or before? Can they survive in Cananea?

The 1500 workers who've lost their jobs have had to leave Cananea, many to find a way to make a living outside of Mexico itself. It's not possible to live in Cananea without a job. That's why I say that it's in danger of becoming a ghost town. There's no other kind of economic development there. There's just a small amount of retail business, and no other large source of work. There were a couple of maquiladoras in Cananea, but they closed because of the problems with the mine.

At the end of the strike as well, the government said that the water system, which had been operated by the company, would now have to be operated by the town. But the town has no infrastructure or money for operating it. We think this is an action against the whole community. They cut off water to the whole town, and finally the women in the town occupied the water pumps and distribution plant and turned it back on.

DB: Cananea is an historic town, and the strike in 1906 was in some ways the first battle of the Mexican Revolution. What would it mean to people in Mexico generally if the town ceased to exist?

Cananea is considered the birthplace of the revolution. It's also been considered a bastion of Mexican trade unionism. With the virtual destruction of the union in Cananea, it's a bad sign for the future of unionism in Mexico generally.

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-