|

|

& Border Jumpers

The Story of

a Bracero

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Rigoberto Garcia Perez

Blythe CA (12/2/01)

DB: Where were you born?

I was born in Lalgodona, Michoacan, January 26, 1934. I'm old. I'm not as old as Figueroa here. He just has more juice than I do. My father was Serafin Garcia. My mother was Rosa Perez. They've both died.

|

|

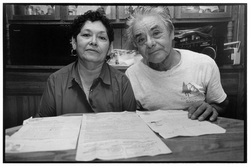

Blythe, CA 12/2/01 Rigoberto and Amelia Garcia, who were born and married in Michoacan. Rigoberto came to US as a bracero in the 1950s. His work contracts are spread out on the table. |

DB: Was your father an ejidatario?

No, he didn't belong to an ejido. He owned some land. But he had to keep selling it off, and it didn't have much water. In the end, he sold almost all of it. He became a bracero when the war started with Germany. I think that was in 1941. He went to Mexico City. He was in Fresno a year and a half, from 1941 to the middle of 1942.

DB: Why did he decide to go - from lack of money, from curiosity, or what reason?

Well, I think for both reasons. He was a real fighter. He thought to himself, well, to get ahead, I should go to the United States. So he did, and it went well. They always made good money, the braceros. He rebuilt his house. He tried to recover his land, because land is worth a lot, but he couldn't. But he was a fighter, so he started a small store and went into business. And he never went to the US again.

So when I began to think about crossing the wire, my father told me "no, no." My mother was always against it too. But I went and stayed a year. I was curious. Other people I knew had gone, and I thought I would go to find out what it was like too. It wasn't just my father who was against it, but my grandparents also said it wasn't worth it. It was as if I had told them I was going to work down in the mine. They said, "you'll get to be dependent on that paycheck. Stay here in your own land. You'll get the money from the crop every year." We were growing camote, avocado, onions, all kinds of vegetables, because my father knew how to grow these things. But you don't see any money until you harvest the product and then sell it. My father said, if you go to the US, you'll get to depend on the check.

DB: How old were you then?

Well, by that time, I had already gone for a year as an alambre (undocumented), but then I was thinking about fixing my papers. I was 24 years old.

DB: When your father was trying to dissuade you from going, how did he describe his experiences in the US?

His idea was that when you work for someone else, you never get free of it. For him, working on the land we were working for ourselves, not someone else. When you work for someone else, the profit from your work stays with them. And because he was someone who had owned land, and knew that the land was able to feed him, that he could be his own boss. On the other hand, if you went to the United States, you wouldn't be your own boss. You'd be the worker for someone else. That was his advice, and it was true. Because here you work just to survive, and you don't own anything. You just survive and survive, but someone else owns your labor. So he would say, you have to be a visionary. You're going to go there, and it will suck you in. Because that's the way everyone lives in the US. There are just a few who control the work, and they wind up with all the money. And they even pay well. And people live well. But that's it. They never get beyond that. They don't have their own land. Even to own your own house is very difficult. Here you have everything, he would say. It might not be worth what you could get on the other side, but it's yours. That was his idea.

DB: When you went to the US the first time, you went as an alambrista, not a bracero?

Yes, I was an alambre the first time. We got to Mexicali, and got on a train. There were two trains that went from San Diego to Phoenix, and traveled a ways on the Mexican side. They don't exist any more - I think they've even torn up the tracks. But in those times the trains went that way. The one from San Diego was for passengers, and the Pachuco was for freight. The Pachuco would go through Mexicali at midday, and the train from San Diego would get to Mexicali at eight in the evening. So you could get on that train in Mexicali, the freight train, and get off in Algodones. You'd make your way to Yuma, and hop another freight there going to northern California.

At the border itself, you'd have to get off. The immigration was there. So you'd get off outside town, and cross the border on foot. Hiding, right? It wasn't a big problem, like it is today, where they're keeping such a watch. The border was almost free then. The big problem was to get the freight train in Yuma. In Niland, the immigration would inspect cars. But if you got off, and went around, you could avoid the migra. They'd be there with their flashlights, looking on the cars for people. But you would already be hiding then. And so when the train started up again, we'd get up out of our hiding places, and vamos. And when the train got to Indio, where there was a big yard, we'd get off again, and the immigration would come again. They'd get whoever they could, but those of us who were more coyotones, we'd get away and hide. And when that train or another one would leave, we'd get on again. And that was the last immigration inspection. Well, maybe another in San Bernardino. But by the time you got to the big yard in Los Angeles, well you didn't have a problem anymore. And you could get all the way to Stockton. We knew which trains were going north. We could tell which train was heading for Bakersfield, and we'd get off there. If it stopped in Fresno, we'd get off there. But usually, we'd go all the way to Stockton, or up the coast to San Jose. Because those were the two places where we knew people, where we had friends.

DB: So where did you work?

I worked in Stockton, in the cherries. They caught me twice there. After that, I didn't want to go back. I decided to work in Calipatria, where I stayed for a year and a half. If they caught me, I was closer to the border, and it wasn't as hard to get back. And I had a good boss, a Canadian named Eldon Rice, I think. His daughter was named Patricia and his son was Bob. They spoke very good Spanish, and were good people to work for. We picked grapes. We picked cotton. We irrigated. And because we were so near Mexicali, when we'd hear on the radio that some famous artist would perform there, we'd all go. We didn't need papers. We'd go to Mexicali and have a good time. And that night, we'd cross back over go to a store three miles away, Compuertas, and get a taxi there which would take us back to Calipatria. It was easy. Now, it's not. Now it's very hard. Now it costs a lot of money for everyone to cross. Poor people. They suffer a lot.

DB: Why did you decide to work as a bracero, if it wasn't so bad to work as an alambre?

Well, I decided to do it because I went back home, and then I got married. And I stayed home a year. Then, one of my brothers who had gone as a bracero said why didn't I go with him as a bracero too. He said, you can work and there won't be any problem. So I liked the idea, and I went to the contracting station they had in Sonora, in Empalme. When you got there, it was very easy to get work. There were people there who would sign you up, for $300 a month at that time. So very quickly they'd get people, a thousand or two thousand a day. So instead of hopping freights and all that, we could go a different way. I went as a bracero four times. And I didn't like it, because once they'd hired you, and you got on the train in Empalme, all the way to Mexicali. In Mexicali, you'd get on the busses, and go to the border, to the old crossing point there. Now they have a new one. And from there, they'd take you to El Centro. Thousands of men every day. From Monday to Friday. And once you got there, there was a very well-organized chain. And they'd send groups of two hundred people, as naked as we came into the world, into a big room, about sixty feet square. Then men would come in in masks, with tanks on their backs, and they'd fumigate us from top to bottom. Because supposedly we were flea-ridden, germ-ridden. No matter, they just did it.

So when we'd get out of there, then quickly, they'd tell us to go to the place where they'd take our blood. They took a pint of blood from every man. Well, it was a tube. I'm not sure how much it was, really. And they'd check us out there. And anyone who was sick, they wouldn't pass. And then they'd send us into a huge bunk house. And that's where the contractors would come, from the associations. From the counties, like San Joaquin County, Yolo County, Sacramento County, Fresno County - all by county.

Others would come from Arizona. They'd come in, and the heads of the associations would say, "Look, line up here." And when they'd see someone they didn't like, they'd say, "You, no." Others, they'd say, "You, stay." Usually, people who were old they didn't want. They just wanted young people. Strong ones, right? And I was young. So I never had problems getting chosen.

DB: Did you go through this experience every time you came?

Every time. Every time the same routine. They hired you in Empalme, and brought you across the border. They fumigated you and took your blood. The people who were in charge of the association never appeared. I always had the idea there was someone big in charge. Someone who decided where to send the people. They'd send us in busses. You were hired in El Centro and given your contract, usually contracts for 45 days.

I think it was an agreement from one government to the other. There were intermediaries, the contractors, who hired the people. But the people in charge were the associations. When someone would arrive from an association, like the association from Stockton, actually from San Joaquin County, where Stockton is located, they would distribute the people between different labor camps. Labor contractors would come. They'd say, for instance, that the needed 40 men, for picking tomatoes, for the cannery. And so your contract for 45 days would be with them. When it was over, they'd put you on a bus, back to El Centro. And there they'd give you the passage back to Empalme. Each contract would last 45 days.

|

|

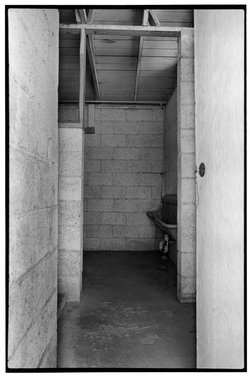

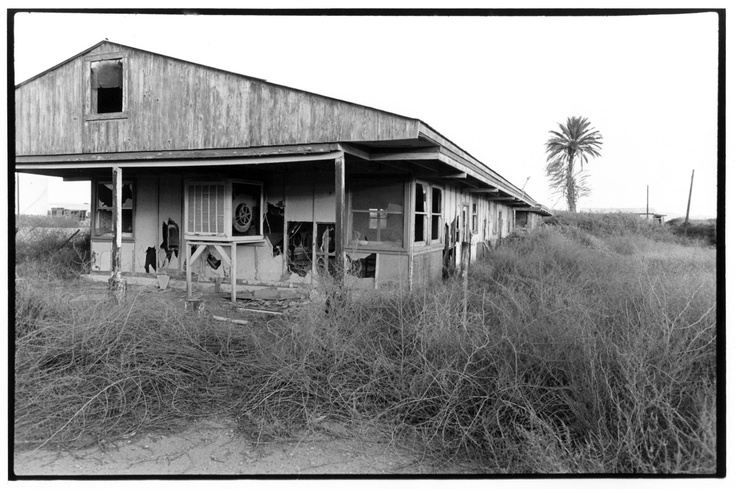

Blythe, CA 12/3/01 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s, which was still used to house migrant farmworkers up until the 1980s. |

DB: You couldn't renew a contract?

Yes, that could happen. One I was in Santa Maria, the second time I was here, and from Santa Maria they renewed us and sent us to Suisun, on the road from Sacramento to Martinez or Vallejo. There's a place there where there's a lot of pears. I don't think it's there anymore. The town was called Suisun. And we picked pears there. And when we were through there, the rancher said, now we're going to Davis. And from there they'd send us back to Mexico. So they renewed us again, and we went to pick tomatoes in Davis. When we arrived first in Santa Maria, we picked strawberries, in April. In July, when the work in strawberries was bad, and we wanted to go back to Mexico or on to another place, they gave us the chance. A friend said, "Let's go! Let's go north!" So we went. They gave us the choice - who wants to go to Mexico, and who wants to go pick pears. So they sent us north.

DB: The contracts had your name on them?

Yes. And the wage was indicated too. I think at that time it was 80¢ an hour. In the tomatoes it was piece work - 20¢ a box. That was pretty good if you could pick a hundred boxes. But the work was a killer, really hard. But that's what you wanted. The boxes were at 20¢, for whatever you wanted to pick. The tomato was very good. They'd give you two rows. And those two rows could give you 50 boxes. And you could do that in half a day. There were people who were really good. I remember in Tracy I was with a crew from the state of Oaxaca, from Juajuapa de Leon. And one of those boys died. Something he ate at dinner wasn't any good, and the kid was poisoned. But what could we do? We were all worried because this boy from Oaxaca had died, because what happened to him could happen to any of us, no? Poisoned by the food. They said they'd left a lot of soap on the plates, or something had happened with the dinner, because others got diarrhea. Lots of people. I got diarrhea too. But this boy died.

|

|

Blythe, CA 12/3/01 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s. |

DB: Did people normally work with others from their home state or town?

Not really, because when you got to El Centro, thousands of Mexicans were there. From all parts of Mexico, people total strangers to each other. For example, I'm from the state of Michoacan. And I was put together with a group from Oaxaca. That's very far from where I'm from, in the south of Mexico. We slept in big bunkhouses. It was like being in the army. One bed on top of another. Each person had their own bed, with a mattress, blanket and so on. Your soap, your razor. Everything in order. They'd tell us, we want you to keep this place clean. It's your house. When you get up, make your bed. And we all did it. We woke up when they sounded a horn or turned on the lights. We'd make our beds and go to the bathroom. Brush our teeth and whatever. We'd eat breakfast, and they'd give us our lunch. Some tacos or a couple of sandwiches, an apple and a soda. Sometimes they'd bring food to the field, and give us a meal there. It all depended. The camps were different. But we worked well.

When we got back to camp, we'd wash up. In the tomatoes, you really get dirty, like a dog. You'd get back and go wash up right away, before you went to eat. You'd go into the kitchen where they'd serve the food. You'd want to go in there clean, with your clothes changed. There were some who wouldn't wash, but the cooks would tell them that they wanted everyone to bathe before they came in to eat dinner. And they didn't want us to come in dressed in a teeshirt.

We could leave the camp if we wanted, for example, to go into town. Someone would ask, who wants to go into town? In Stockton there was a man who had a drugstore and a radio station. He was a Spaniard. And he would send busses out to the camps to give people a ride. Clearly, he was making a business out of it, since he'd sell shirts, clothes, medicine. There was a store in town we'd go to called Las Marianis.

So I had come as an alambre, and then back came as a bracero. Eventually, I bought a car, got a drivers licence, and lived like any other person. But I always remembered how I got here. Illegal, a bracero. And I began living in this country. And here I am.

Afterwards, I brought my family, and now I have nine grandchildren. I still have a house on the land my father gave me. And I haven't let it go, because that's where all my children were born. People ask me why I don't sell the house in Mexico, but I say, "No, no. I was born there. Anytime we want to go to Mexico, we have a place there." I tell my son, your grandfather was a visionary, and my mother also thought about the future. Although you're very poor, and don't have much school. Don't sell it, my father said, because one day we don't know what will happen. Maybe we'll go back.

DB: How did the foremen treat you as a bracero? How did the people living in the community around you treat you?

The foremen really abused the people. A lot was always expected of you, and they always demanded even more. But we were all working out of necessity. We were obligated to really move it. The people in town were used to seeing us. They didn't discriminate against us much. Actually, that happened to me later, when I had my papers. After working in the cherries in San Jose, Gilroy and Stockton, a friend of mine from Veracruz and another man, a Frenchman, asked me to go with them to Oregon. So we went to Salem, the capital of Oregon. I'd already been through a lot, and the idea of sleeping under the trees didn't appeal to me. They'd give us a tarp to put up as a shelter, and expected us to sleep on the ground. I didn't like that. I thought - we'd been there for three weeks, sleeping on the ground. If we did more of that we'd be dead. So four of us - the guy from Veracruz, the Frenchman, myself, and one other decided we'd look for a house in town. The Frenchman had a car. So off we went.

But we couldn't find any house because we were strangers there. That was in 1963. There weren't any Mexicans there, and people would just stare at us. And the Frenchman, because he spoke English and was white, even he agreed that in that town they discriminated against Mexicans, and we'd have to go back to sleeping in the field. But no, we really didn't want to. We were going to just go back to California. But in this town there's a big bridge, and with luck, we found a little place near it. So we sent in the Frenchman first, because he was white. You know, white with white, it's different, no? So this old woman came out, and she said she had a garage, but she didn't want to rent it to us. The Frenchman said, yes they're Mexicans, but they're good boys. She said, no I don't want Mexicans. They'll just rob me. Finally she agreed, but said she would only do it with conditions. We said, "anything, we'll agree to anything." She said, "when you come home from work, I don't want you to go outside. If you have to go to the store, you tell me, 'We're going to the store.' I don't want people to see that I'm renting to Mexicans, because they'll call the police." We said, "OK." So we'd stay inside when we got home from work.

When the work was finally over and we had to leave, the lady cried. She asked us to forgive her. "I'm old and I'm going to die," she said. "I thought ill of you. I had bad information about Mexicans. I see now that you're very good people. You work hard, you don't drink. You're young, but if you were bad, you would have been out looking for girls." I told her, "In Mexico I'm married. I have two daughters. I can't go out." She said, "You're here by yourselves, but you're good boys." She cried when we left, and she gave a little package to each of us - a little suitcase, with some clothes. The Frenchman stayed behind, and we bought another car and went back to California. He said that he'd been in Korea (he means Vietnam), and that when the French left, the gringos came in. They'd been beaten, and he said, they'll beat you too. The rich people from there left to Buenos Aires and all over the world.

DB: So you worked four years as a bracero?

I was a bracero from 56 to 59. I was in Watsonville six months before I got married. That was when my wife and I were just lovers. We'd write each other, and I'd ask her to wait for me, until I returned. So we got married, and here we are.

|

|

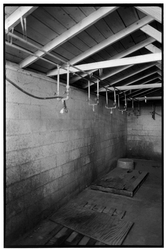

Blythe, CA 12/3/01 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s. |

DB: So what did your wife think about your working as a bracero, and being away for such a long time?

She didn't like it, but she stuck with it. We were building a house in Mexico and we wanted to do something. I told her, "I'll just go this once, and I'll be back in time to do the planting. We were planting corn, and vegetables too. We rented irrigated land, and we were getting everything ready, cabbage, lettuce, onions, peanuts. Chile too. I went off to work, but always with the idea I'd come back and we'd use the money to do more. We had four hectares of onions. It was beautiful. But the price fell. And the crop just stayed in the ground. At that time, it was selling for a peso a kilo. And we had tons and tons. But suddenly there was a surplus of onions from other valleys, and that was it for the onions. So I said, "Well, I better go to the United States." The next year, when I came back, we were going to grow camote too. And we had a good crop. At that time, not a lot of people knew how to grow it. It took a lot of work. So we put our backs into it, and irrigated, and we had no competition. We were the lords of the market. But afterwards, I thought again, "Well, I better go to the United States." A human being is never satisfied. We all have one thing, and want another. I told myself that what I wanted was my house and some land. And I did that. But I went to the United States, and when I got my papers fixed, I brought part of my family here, and then another part, and then I bought a house in Ventura County, in Oxnard. I had it for 16 years. Finally I sold it. All of my children have their own homes, so I sold it and bought a car. So here I am living in this trailer. I spent everything on it. But I'm still working and I live comfortably here in this country. I've lived well in both countries.

DB: When did you decide to live here permanently?

When I fixed my immigration status. I decided I wouldn't go back, because my father had died, and I decided to bring my wife here instead. I was tired of being alone. I thought, why am I leaving her there? I thought I'd bring her here. And then she didn't want to go back either. So the two of us were here then. When I was living in Oxnard, and I'd fixed my papers, my wife went to the US embassy in Mexico City, and filled out applications for herself and Letty, my daughter. At first they wouldn't give one for Marisela, but I told my wife to stay there until they gave her one. How could we all go to the US and leave her behind? So she went back. And you know how you have to bring all kinds of papers to the embassy with you - birth certificates, Mexican passports, everything has to be there - she asked where they expected us to leave our child if she had to stay behind? So they spoke with a consul, and he asked her, do you want to go with your papa? He asked her about her papa, and she told him he was in the US, that he sent money back home, everything. Finally he said, "OK Marisela, I'll give you the visa." And they gave it to her.

So they went to Mexicali and phoned me, and I came and got them, and they stayed two months with me. We went to Oregon. We had a car, and we wanted to see Oregon and Washington, Hood River. We went picking cherries. And when the cherries were done, we went to Tijuana. I had left three other daughters with my sister in law. We had to arrange papers for them. The youngest one was seven years old. When we finally got papers for her she said she didn't want to go live in the United States. She wanted to go home. We all tried to tell her how great it was, that we would put her in school. She said, "I'm already going to school." We said, "Yes, but we're going anyway." So she came, and now you should see how many degrees she has. She lives in Santa Ana, and just married a man from Germany. He's a good boy, named Esteban. When she graduated from the university, she went to Europe. She went all through Europe, and even had a boyfriend in Paris. But she got rid of him, and then she had another boyfriend, a lawyer from Oxnard, a Mexican.

DB: What were the hardest things about your four experiences as a bracero?

The loneliness, because I was young. And more than anything, homesickness. You have the security of three meals, a place to stay, your job. But you get depressed anyway. It's like being in the army. At least I think so, because I never actually was a soldier. I was drafted in 1962 in Ventura, but I never had to go. They gave me a BA. So I don't really know, but I think soldiers can't be very happy either, because they're always lonely. They're all men, just like we were. So you miss your land, your wife. And since I met my wife, I can't go with another woman. My parents and grandparents gave me that tradition. One wife for one strong family, right? Even if you're poor, and live 80 or 100 years, don't get rid of one wife to find another, and another. That's like living like an animal. So that's what made us cry. My wife and kids.

It was important to send them to school. And even though they had schooling we still lived in a small village. And we cried about that. So you keep going, thinking about it. What should I do? The youngest ones have gone to school here, and speak good English. They have good jobs. If they had gone to school in Mexico, they wouldn't have had the same chance. Economically, you can pay for a good school, and that's what I was trying to do as a bracero. I wanted a real future, and we knew that we were just casual workers - I would never be able to stay. I had to look for another future. And I found one.

The last time I came as a bracero, I was in San Diego. When I began working that time, I said to myself that it was time to fix my immigration status. And there I worked for a Japanese grower, who did all the paperwork for me. He was a good man. He'd had a bad experience during the war. They had put him into one of the camps. He talked a lot about it. He told us, "I know what your life is like, because we lived that way too, in concentration camps. They watched over us with rifles." So he got papers for all of us. He fixed us up, and told us to come work with him. That's how I got my papers. His name was Suzuki. That was in 59. That was the last contract I worked.

DB: He obviously thought you weren't really free living in the camps. Was he right?

Oh yes. We were working on contracts, and living in labor camps on the property. There were rules we had to follow. Not prisoners. But we had to live there. And he said, "You're good workers. I feel for you because I lived in a place like the one where you are. When I was a child, with my parents, where they watched us with rifles. Here they don't watch you with rifles, and you can go to San Diego. But I know you're not happy, and I'll help you get papers. Go to Mexico and get the documents you need." And he did what he promised. So I came back, and went from San Diego to Oxnard, where I was a foreman for him.

There were Japanese braceros at that time, and some of them worked for him. He was growing pole tomatoes at that time. He told me, "Look Garcia, even though you're working four hours, I'll pay you for twelve." The Japanese were different. They all had a good education. They were just trying their luck there. They acted wild, and one of them would get drunk. When he'd come back drunk, I'd tell him not to drink, because Suzuki didn't like that. But he didn't pay attention to me. Suzuki told me he didn't respect me, but not to worry about it. He said, let him come drunk, don't get into a problem with him. Let him say what he wants, don't get into a fight. I've put you in charge of the people, in charge of the Mexicans. They all do what you ask. Let the others do what they want. I'll be sending them back to Japan anyway.

DB: During this time, did you ever hear of any strikes or labor disputes involving braceros?

Yes, there were places where they went out on strike, or stopped work. They really abused people in some of the camps. I was never in a strike myself. But I heard about them, and one of my brothers was in one. He went on strike in Phoenix. They threatened them that they would send them back to Mexico. They put them on a bus to El Centro, and from there they sent them to Fullerton, to work in the oranges. It was because of their strike. They struck because they were picking cotton and the crop was bad. I never picked cotton as a bracero. But they always said you could never make money doing it. A lot of work for nothing. That's why they went on strike. But I heard about them in other places too, including here in Blythe.

On the contract it even has to have the signature of the mayor of the town where you're from, guaranteeing that you have a good reputation. You also had to have experience picking in Mexico. In those times, they were worried that people were abandoning Mexico, that there wouldn't be people to pick the crops there. So they made it a requirement that you had to have picked so much time, or so many pounds of cotton in Mexico, in order to be able to come to the United States. It was a kind of blackmail. My wife's father had to work in the valley of the Rio Yaqui, near Ciudad Obregon, to complete his period of time, before he could go to Empalme and sign up. Her father is 94 years old now.

|

|

Blythe, CA 12/3/01 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s. |

DB: Can you describe this strike in the cotton a little more?

My brother didn't organize it, he was just part of the group. There were leaders, but I don't know who they were. But he was one of them. He got it into his blood, and he later was with Cesar Chavez for many years. I was too. But it was really about exploitation and injustices. There was always exploitation then. They would say that a bucket would by paid at such and such a price, and you'd fill it up, and then what? When the movement of Cesar Chavez came along, we already knew all this. We'd heard people who'd participated in these movements. And it was good.

For example, when my father came to the United States in 41, there was an eruption of a volcano in Michoacan, called Paracutin. The lava flow went into Zamora. The lava spread over the land around the church, that the government had taken over after the Revolution. It was land of the government then. Today the church has taken it back. Anyway, they put people to work to break up the lava with sledgehammers. And they would haul the rock away. But they paid very little for this. So they had a strike then about that too. They organized themselves, and a union helped organize them. I was only seven years old. I saw it all though, about the union and everything. That they didn't want to pay the people. I heard all the talk. I heard them say they had to go on strike. The boss didn't understand when they would talk to him. They said they had to hit him where it hurt, in his pocketbook. If you don't hit him where it hurts, he'll never listen to you. He won't see you. I think it's that way everywhere in the world.

It's like now with the people who make the stoppages. They have to sit down in the highways and stop the traffic. Surround the city halls. Because the government won't listen to them. That's why there's a different government in Mexico now. And I think that's the same all over the world too. The strikes now and the ones when I was a child — it's the same thing. For a human being, that's the way it is. Those who can exploit, do it. That's why Cesar said when he died in San Luis, "Look boys." He gave us an example. "Hay que educar a que pisa, y hay que educar a les deje pisar. Hay que educar a los dos. There are those who pisan, who exploit and who violate your rights. That's the way they are, because they were born with money. They know nothing of poverty. You have to educate them. That they have to respect other people." And that's true. That was a very wise thing to say. You have to educate both. The exploiter and the exploited. It's like a marriage. It's simple. If you don't educate both sides, you can't have a marriage. You can't have a future.

DB: Have you found a lot of bosses you've been able to educate in that way? Isn't that a little difficult?

It is difficult to educate a boss. It's more difficult, because normally a boss is born that way. Born powerful, right? He doesn't know anything else. If I tell him that I'm dying of hunger, he'll say, "Yes, I see you. But I have to eat. I have to have what I need. I have to buy clothes. I have to have the freedom to do that." So long as he's doing OK, he'll ignore anyone like that. That's the way bosses are. It's very hard. The person being exploited, they can be educated. The bad thing is, they'll buy someone, and take away their ideals. Their desire to push or struggle. That's what happened with the Mexican system, with the PRI. The leaders would come and say, "Let's go vote for so-and-so for governor. For president." They'd give you your lunch and your ten pesos. "Let's go," they'd say. And look at what they were buying us with. That's what hurt us for seventy years. There were revolutionary people, who never fell into that trap. And my father was one of them. Because he had land. He'd say, if all the people who died in the Revolution were to wake up, they would really punish them. The people who came out on top in the Revolution became millionaires. They're not doing what so many people died for.

I went to Stockton and old Sacramento and old Lodi, when so many of the people who'd gone to the war in Korea came home. They were all leaning on the storefronts, just winos. They came back from the war, their wives had all remarried. They had no children. These people became disillusioned. Think of how many people had died and lost their families. And they fell into alcoholism. And after that stage came drug addiction.

The same thing happened in Mexico, to the people who survived the Revolution, for example my father and grandparents (one died in the Revolution, and the other in Delano - they killed him there) Despite all the people who died, who struggled against the injustices of the powerful, it all just came back. That's the history. It's the law of life.

DB: You don't see hope anywhere?

Yes, of course I do. It's just not the way we wanted things to be. For example, Figueroa here, has his house. But how many acres does Fisher [a big rancher in Blythe] have? 1800 acres. I just wish he'd give ten acres to me. Just imagine. But that'll never happen. I live OK, but not as I wanted.

So in Mexico, people struggled for their land and everything. And they wound up just owning their house. There were people with thousands of hectares, but who wound up with that? They were supposed to redistribute it, that was the Revolution. Here, the Revolution was different. With laws and everything. Laws that should have been respected.

In the strikes I was in here, for example, the strikes in Firebaugh, there was a line of sheriffs there, all from Fresno. From Los Baños. And their line was taking care of us. And on the other side were the strikebreakers. Those who were on the bosses' side. If the sheriffs hadn't been there, they knew what would have happened. There would have been someone killed, or more than one. So in some ways, their presence was good. If they had left people free to do what they wanted, what then? Because we react like animals. For their interests, they would kill someone.

DB: A last question. What are your conclusions about your experience as a bracero?

It was the beginning of the life I'm leading now. They were good experiences, as I explained, because we survived. Thanks to those experiences, we survived. I found a good boss, and here I am. I can't ask for more. I have two countries, just me, one person. I can cross the border, and live happily in my land. And I can live happily in this country too. Because, with me, people have been marvellous. And now I have a brother-in-law in the White House. [Laughs]

- Braceros & Border Jumpers

- The Story of a Bracero

- Two Braceros

- The Story of a Union Organizer

- In the Mexican Desert, a Sanctuary for Border-Crossers

Top of Page

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-