|

|

& Border Jumpers

Two Braceros

Celestino & Amelia Garcia

Eusebio Melero

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Celestino & Amelia Garcia

San Leandro CA (11/20/01)

Amelia Garcia's comments are in italics.

DB: In what year were you born, Mr. Garcia?

Well, I think in February of 1916, in Sandias. I was registered in Tetewanes, a municipio in Durango.

He was born the 6th of February of 1916, during the Revolution. I was born in 0ctober, 1920.

|

|

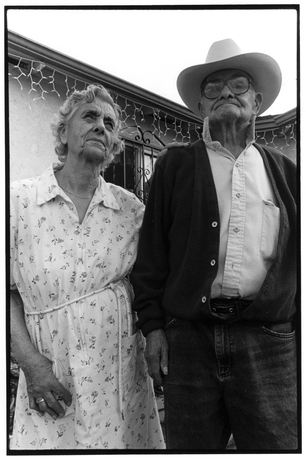

San Leandro, CA 11/20/01 Celestino and Amelia Garcia, who were born and married in Sandias, Durango. Celestino came to US as a bracero in the 1950s. |

DB: Your parents worked on the farm?

Yes, in Sandias.

DB: When did you come to the US for the first time?

About the mid 1940's. People from Sandias were going to the US then. They would solicit people and gather us at a certain location. There they fixed our papers so that we could come here to work.

In 1941 we got married. [She laughs]. That's why he came here - we got married. But he had come before. In the place people were being gathered, they say that if someone fell, they would die because there were so many people there to sign up. I still stayed in Mexico during that time. The contractor, the owner of the work over here, was from our same town. And he was the one that gave orders. Leonardo, right? Leonardo Galindo.

Yes, yes. But he never came with us. He was there waiting for us. He was a boss.

DB: Galindo asked you to come here?

Yes. They would put us in the trains in Mexico and bring us up. And once we got here, He would take us off at certain places where we were needed. Leonardo was working in Woodland.

DB: Why did you decide to come here?

Because it was better working here. We would earn more money and we could save.

But it was only seasonal. They would only give you how many months? And then you'd have to go back to Sandias. Not the whole year.

About 6 months we would stay in the U.S. Then they would send us back. But if someone didn't want to go back, sometimes they would leave him here to work. But normally, you would go back every 6 months.

DB: Was the work hard?

It was somewhat hard. In Santa Paula, where we went first, we picked lemons, oranges - that kind of fruit. We worked there about 4 months. We lived in a camp, but it was not very big. We had work partners there who were also from Sandias. Sometimes it was good and other times it was bad. The little that we earned, we would send to Mexico for the family. We just had a little bit of money here to go around.

He made a house. With the money from the first three trips he made to the US, we built the house. We got married in 1941, after his first trip. Eventually we got documented and came up together. Thank God, we are citizens now. [They both laugh].

We got fixed. Because I came and worked, they said that we could get our papers fixed.

It took a long time, though. By the time we got our papers our youngest son was 14. I remember that we came over here the 4th of May, but now I've forgotten the year.

DB: So for years he would work here and you lived over there?

Yes. He would send money for me to live on. It was difficult. They paid them very little at that time, but he would send what he could. And that's how we survived. We suffered in Mexico and he suffered too.

DB: How did you feel being so far away from your family for good portion of the year?

Well, the most that we stayed away was for a year. When I finally got the papers fixed for my wife, I brought them up.

DB: So what did you think of the bracero work? Was it good or bad?

Well for one part it was good because people could come work and immigration would not bother you. When we didn't have a passport, sometimes we would only work for about a week or two and we would get deported. Other times when I would come up. I would work 4-5 months and if they didn't catch me, I would voluntarily go back home. And if they caught me while I was leaving, I'd tell them that I would go voluntarily. Sometimes they'd say, "Okay. Go ahead". Other times they'd put me in jail for one or two days. That happened to me in Oakland. But they didn't do anything more than just send me back.

DB: Do you ever return to Sandias?

At first we would return often, because we had a sick daughter who was mentally ill. Now we go back every year or two. The whole family is here. Sometimes we go back to check the house. We still have a nephew and a brother there.

DB: Are you citizens of Mexico or US?

We are from this country (the US). We are Mexicans still because we were born there. But we are US citizens. We consider ourselves both Mexicans and North Americans. Because we were born there and we love our country and here because this is where we make a living. That's where he made a living. Otherwise think of how much worse off we'd be.

DB: Do you believe that there's a future for your family in Mexico or here? Will the next generations live here?

Most likely here. We have 6 children. 5 daughters and 1 son. Right? I better not get confused. [She laughs]. We have around 11 to 14 grandchildren, and great-grandchildren too. [They laugh]. We're getting old.

It's better here because there's no work there. There's nothing to do.

There are no jobs in that town. When it doesn't rain, there is no corn. There's nothing. Most of the people come here to work.

But why are you asking us these questions?

DB: Because I'm trying to make a historical archive about the experiences of the braceros for a book and a magazine article.

Well, I guess that's OK. It's good to have memories.

Interview with Eusebio Melero

San Leandro CA (11/20/01)

DB: Where were you born? What kind of work did your parents do?

I was born in Durango, Mexico., in the town of Sandias, in 1924.. My family worked as farmers. We lived on a farm and took care of animals. We worked with mules and all kinds of animals. They had their own property, and owned everything they worked with. They didn't work for anyone else.

DB: Did your parents live there until they died?

No, my father died in Tonopah, Nevada in 1936. He left to go to the mines there because he needed to work. I don't know what kind of mines they were. He only worked there for a short period of time, and then he died of pneumonia He died because of the dust. He worked a lot and it was very hot, and he got pneumonia. I was 12 years old when he died.

DB: How did your father's death affect you?

A lot. My grandfather took care of me. There were five of us and he watched us all until we started working. He lived in the same town as my father - our houses were close together. My father and I didn't have a close relationship because he liked to be all over the place. I was closer to grandfather.

DB: How many years did you go to school?

There was only an elementary school in our town, so I went to school there. But there wasn't a high school. I was 12 or 15 years old when I finished school.

|

|

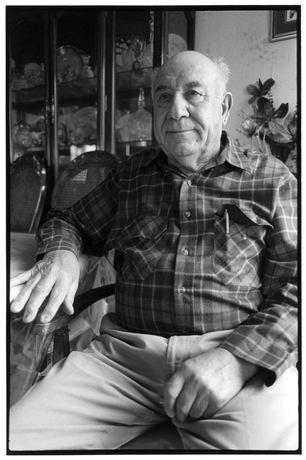

San Leandro, CA 11/20/01 Eusebio Melero was born in Sandias, Durango, and came to US as a bracero. After many years of work he brought his family, got a job in a warehouse, and retired with a pension from the longshore workers union. |

DB: How did you come to leave Sandias?

I came here to the United States when I was 19 years old for the first time. I thought I had to live life. [He chuckles a little bit]. There wasn't much work in Sandias in this time. There would only be work for short periods of time and it would be over. I felt fine about leaving because I was going with a few people from the same town. We were about 5 to 10 people traveling together. We knew each other. I guess there weren't enough people during that time to work in the fields in the United States to pick the oranges and the rest of the crops. So they brought braceros from Mexico. They brought a lot of people from Mexico to work on contract for 3 or 6 months. We signed the contract in Mexico City. People would gather to get a contract and then thousands of us would leave from there.

DB: What did your grandparents think?

Well, my grandfather had passed away by that time. My mother was left with five children and I was the oldest. I left to look for money, for life, to help my family. This was in 1943, and I was 19.

First we went to Mexico City. The contractors that were recruiting people there scheduled a time and a place to meet to enlist us with our birth certificates. Then they'd examine us to see if we were good to work. If not they would return us.

Then from the capital, they brought us to Pasadena, California, in a train. There were hardly any buses then. When we arrived the train was full with people. Once we got off in Los Angeles, the rancheros were waiting for us there. They brought those they needed to Pasadena, Glendora all near Los Angeles. There were many areas and many people at different places. I was taken to Salinas. When we got to where we were going, they had a camp ready with lots of beds. A boarding house for us. We started working there. Each rancher had a specific number of men they wanted, and they would take 6 or 8 of us to the place every morning where we worked. Every day they'd give us our lunches there. We'd go to work and come back at the end of the day.

DB: Who did you work for?

I remember the foreman's name because he was Mexican, although he was born here. His name was Luis. He was a short man and dark complected. He'd already lived in Los Angeles and spoke English. He was our boss. He was a good man. The farmer was a good man as well. During that time, they treated us very well.

We lived in a workers camp, like a military camp. It was a big barrack with many rooms. I think around 100 men lived there. We worked at different farms. Each ranchero had 8 to 10 workers. All of us were from Mexico. Every morning, Luis would take us to the farm to pick oranges. The work was heavy because the trees were too tall. The ladders were 24 feet long and not steady. Sometimes the ladders would fall. We would use scissors, not our hands, to pick the oranges. Also the bags were long and big. When the bags were full, we could hardly get down.

DB: Did they pay you well or badly?

I don't remember exactly how much they'd pay us, but they'd pay us by the box. At that time, everything was cheaper. The little that they paid was OK because the food at the camp was cheap, and they didn't charge us to live there. The food was mostly American and Mexican. It wasn't very good, but OK. They paid every week, and took the money out of our checks.

All of us in the camp were Mexican. There weren't any Filipinos there at that time. We had Sunday's off, and we'd go downtown. We'd just go out to buy a shirt or a pair of pants or whatever we needed.

Sometimes women would come out and look for men at the camp. They were street women.

DB: How long did you work picking oranges?

Just a short time, because then I left to work in Los Angeles. I started working where they ran the streetcars. I worked there for about a month, when immigration deported my friend and I.

We thought there was more money outside working without papers then working on the farm as a bracero. We were looking for more money. It was something a lot of people did. Most people would work for a month or two, and then they'd get out and work somewhere else until they were deported. They didn't do anything to us because we just worked. We didn't do anything bad. We just looked for a better life.

We picked up along the tracks, fixed the railroads. It was good work When you're young you can work well. It was different from the farms. In Los Angeles they only gave us the job, and we had to feed ourselves. I lived with an uncle, who'd been living many years in Los Angeles with his family. Back then there were many jobs because of the war. The city was full of work in various places.

DB: During those times did men from the Marines or the army sometimes fight with the Mexicans in Los Angeles?

It could be true, but I didn't know about that. I wasn't out a whole lot. I focused my time on working. During that time in Los Angeles, there were people known as the pachucos - people in gangs. They had long hair and wore long chains. They never did anything to me. Mexicans and people from other races were in gangs, like some people still are now. We didn't live there long enough to get involved. We hardly knew the area. We didn't speak English then, and I still don't.

DB: What did you think of the US during that time? Did you feel isolated or like you were a part of the city?

It was a little different from back home, but not that much. Here there was more work, but it was still manual work. Everything was done with your hands and your lungs. I don't know how to explain it to you. I lived life as a worker, and life here was good. I liked it here. At the beginning I always wanted to better myself and return to Mexico. But then I started liking living here too much to go back.

DB: That change - was it something that took years to realize?

Many years. I came here many times without any papers, without anything, to work. Sometimes I'd get deported and other times I wouldn't. But I liked life here because it's easier to live here. In Mexico, it hardly rained and water was limited. When the water was gone, we moved. There's little water in Mexico and you don't live as comfortably. When I would get deported, I would go back to my home town and return that same year.

|

|

San Joaquin Delta, Stockton, CA 7/19/95 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s, and which was still used to house migrant farmworkers up until the 1980s. |

DB: Did you return as a bracero?

Yes. The next time I went to Canby, California, near Klamath Falls, Oregon. I was at the border between Oregon and California. There were even people there from my home town. We didn't live all together - some lived in the same town, others were further away.. But we'd see each other every month, and we all worked on the same railroad line. I worked there for about a year, on a bracero contract. I was brought directly from Mexico, but it was to work on the railroads and not as a farmworker.

We had sections with homes in certain spots. There we could cook and do everything for ourselves. It wasn't like in the camps, where there were cooks. There were camps for the railroad, but we weren't in one of them. The boss lived in the same area we did, but in a different house. Everything was separate. There were about 12 of us.

We lifted up the tracks, removed old ties and replaced them with new ones. Our contract was only for six months, but they gave us permission to do another contract for another six months. When I left, the war had already ended. This happened at the end of 1944. I think I was working for Southern Pacific.

If they liked the way you worked, they'd renew your contract and if they didn't they'd tell you that you'd finished your contract and that you needed to go. But at the end of our second contract there was no more work and we returned to Mexico. Then later there were more contracts, but not on the railroad.

- Braceros & Border Jumpers

- The Story of a Bracero

- Two Braceros

- The Story of a Union Organizer

- In the Mexican Desert, a Sanctuary for Border-Crossers

Top of Page

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-