|

|

Trincheras

Some

Chicano History

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Alfredo Figueroa

Caborca, Sonora (11/12/01)

DB: Can you describe the history of your family, especially their connection with Joaquin Murrieta and the gold mines?

I was born August the 14th,1934, in Blythe, Ca. My mother was born in Arizona, on the reservations of the Colorado River Indian tribes. My grandmother, likewise. My great grandmother was married there in Ehrenberg, a port town right across the river from Blythe. Her husband was called Marinero, because he used to work on the steam boats which used to come all the way up from Puerto Santa Clara down on the Gulf of California, all the way to Callville above Lake Mead. That was before the dams.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 Alfredo Figueroa in Las Trincheras during the fiesta celebrating the birth of Joaquin Murrieta. |

Her mother, Maria de Los Angeles Reyna's mother, my great great grandmother, was Teodosa Martinez Murrieta. She was born in La Cienega a little mining town, the first gold mining town of northwest Sonora in the Desierto de Altar. This area was called the Golden Triangle because they had three large placer deposits. The La Cienega mine started in 1740. Most of the gold miners were family, and when the Murrietas came, they came because of the gold. The first Murrieta was a soldier, who came to the Presidio de Altar.

The main headquarters of northwest Sonora was in the Distrito de Atar. Teodosa Martinez Murrieta was a cousin of Joaquin Murrieta. When they went north, she went with all the Sonorenses. There were 10,000, according to some of the historians. The Federal Census of 1850 taken in California substantiates the fact that these were the people from Sonora, although in the census it just lists their nationality as Mexico. But very few people came from the south of Mexico at that time, so we know that they mean Sonoran people because they were the gold-miners. So my history is all tied in with mining.

Joaquin Murrieta was a gambusino, a placer miner. My mother's family were all mixed in with the Chimahuevos, one of the Colorado Indian Tribes. My brothers and I didn't enroll because my grandfather never wanted to. He said he didn't want to be under the yoke of any form of government, because he wanted to be free to roam. That's why we never did enroll in Parker.

My father was from El Rio Yaqui in Sonora. His family came here to the Desierto de Atar in 1905. He worked all the mines all around Trincheras and Caborca. The first time he came to the US was in 1918, during the Bisbee strike. The Wobblies had a big strike there, and a lot of the miners that came from Mexico were deported - any foreign miner that had anything to do with the union. And my father joined the union. My grandfather, prior to him, worked in Cananea, and was involved in the early strike there in 1906.

So through both sides we had al lot of miners. My father was a Yaqui Pima, and very independent. He used to tell us that your biggest enemy was your boss. And his father, all that line, were from the Rio Yaqui, towns called Tonichi and San Jose de Pima. Really, Figueroa is a Basque name. And the first Figueroa came to this area in around 1725. They say that first Basque was a tax collector. He married a Yaqui and they ousted him from the Figueroa clan because of it. But they started intermarrying with more Yaquis and Pimas nevertheless. My father used to speak Yaqui. And he used to dance the Pascola and the Matachin. He was very independent and when he saw any injustices he would intervene and protest.

He got a job in the mines as a young man, barely 18 years old. The strike started in Bisbee, and he just got involved because everybody struck. Whether he wanted to or not, he had to participate. After that he worked in other mines in Jerome, in Ruby and in Globe-Miami, Arizona. He worked in Sonora Rey Arizona, called that because Rey was the Anglo town and Sonora was the Mexican town. They had a big strike there too, and he was involved in a more responsible way. They closed the mine in Rey, and he and his two friends left. They were gonna go to the big mines in Jackson California, the gold mines, and on the way they stopped in Oatman, Arizona, where my mother's mother, Dolores Mollinedo had a boarding house. The house is still there, one of the few adobe houses. My father stayed there to get a job. His two friends, Domingo Duron and Tirsio Ahumada left for California, where the Colton cement and limestone mine was starting up. There in Oatman my father got married to my mother Carmen in 1927. In 1965, my father was real sick with silicosis, and we took him to the hospital in Riverside. And who was there in the hospital? Ahumada and Duron! Can you imagine? The three were all sick from the same thing. Their lungs just deteriorated. My father died of silicosis. His lungs were full of clots. Blood would come out when he spit.

My older brothers were baptized in Llano, a small town south of Magdalena in Sonora. They were baptized there, and that's where my grandfather on my father's side was buried. My grandmother on my father's side is buried in Caborca.

DB: So did your father want you to follow in the same life he led?

He never wanted us to work in the big mines. We were gambusinos, small mine operators. The average life of a miner is not that long. My father liked to be on the surface, placer mining and panning for gold. He was very successful in looking for gold because he was a connoisseur of minerals. In Mojave County he would always win the prize for knowing just by looking what kind of minerals a rock contained, and what the percentages would be roughly. He would always get the blue ribbons. He wasn't a geologist, but in the old days, if you wanted to study to be an engineer or a geologist, you'd have to go work with some of these old timers like my father. In the mines you had to know how to timber, to make the stubs, the raises and all that.

|

|

|

|

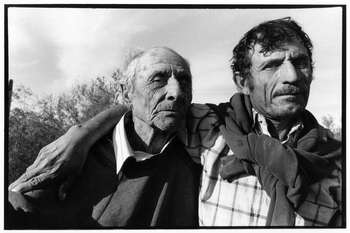

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 Alfredo Figueroa and townspeople of Trincheras. |

DB: When did the kind of mining your father did begin in California?

The first big gold strike was there at Santa Clarita Canyon, just north of San Fernando, in 1841, made by Sonoran people. They lived right south of there - all they had to do was cross the desert. Then they continued moving north through California. These guys were gold miners. They pursued the gold, and they didn't wait for 1849 to come to the gold mines in California. They were working a lot of mines prior to that.

When the Sonorans didn't find too much gold they would go to look for a new strike. That's why people are still working right here in Trincheras, in the Golden Triangle, because of some of the gold was left. The early miners were greedy - if they didn't find that much, they'd go to the next gold strike. They were always looking for the big gold strike. The original miners reminded of the migrants when we used to go pick grapes in Delano, or pitch watermelons in Bakersfield. The miners did the same thing. They would cross the Desierto del Diablo from Sonora to Yuma in the early spring, or maybe late winter before it got too hot. And they'd come back in the late fall or beginning of winter to Sonora. It was the same migration of people - up and down, up and down. They never wanted to leave their place of origin. But that stopped in Joaquin Murrieta's times -1852, 1854. The people were forced from the gold fields. The Anglos just wanted them to get the hell out. That was the main purpose of the Foreign Miners Tax Act, approved by John Bigler who was then the governor of California, and enforced by the vigilante committees in Tuolomne and Calaveras Counties.

People don't migrate to the mines anymore. I would say that really stopped completely when the Second World War started in 1941. They had a law passed that no dynamite was allowed for mines that were not for national defense. We were able to continue mining after the forties because we were mining maganese. Manganese, copper, and lead were minerals for national defense. I worked 11 years in the manganese. And in between I worked some lead and copper. But the bulk of the miners' migrations closed down at the beginning of WWII.

DB: Teodosa Martinez Murrieta must have been a pretty remarkable woman to go with the miners from Sonora to California.

She was a very strong woman. My aunts used to hate her guts because she was just so cruel and mean. She died at 107 years old, in 1931, and was buried in Parker, Arizona. She had a homestead on the river at Parker, and her family worked the mines there - McCracklin, Signal and others - real good mines. But then my great great grandfather got old, and they started planting vegetables. The railroad passed through, and they would sell vegetables to the railroad towns. One day, my great great grandfather took his cart and all the vegetables to town, thirty miles away. He didn't come back for more than two weeks. He had 19 kids, and it was bad. They didn't have anything to eat because he'd taken most of the food down to Wendon. So my great grandma sent my uncle to see her mother, who was working at a boarding house in King of Arizona, in the Koffa mountains between Yuma and Quartzite. And sure enough there was the old man, drunk as a skunk with a bunch of leaches that used to hang around there and wait for this poor sucker to show up. She got him with a shotgun, tied him up in a buck board, and told him, "Next time you abandon your family, I'm gonna come and kill you with a shotgun." She wouldn't have hesitated to shoot my great great grandfather. She was tough and rough. My great grandmother had a stiff arm because they say that one time my great, great grandmother got mad at her and threw her against a wall and broke it. We know she was just a meany. When we hear that she came the first time in 1847 to California with all the guys from Sonora, we know that's pretty close to the truth cause she was one of those hard ladies.

She used to say, according to my uncles, that she was Joaquin Murrieta's cousin. They were part of the Murrieta family. There were very few Murrietas that came at that time - just three men - Salvador, David Jose, and Juan. Juan was Joaquin Murrieta's father. Those are three that spread most of the Murrietas that we have right now. They really came from San Rafael de Los Alamitos.

|

|

Blythe, CA 12/3/01 An irrigation canal from the Colorado River, where the Mexicanos and Chicanos of Barrio Cuchillo bathed and swam. |

DB: So you learned all this in your childhood?

I think I had the most wonderful childhood anybody could ever think of. I was born in Blythe but when my the mines opened up again we went to Oatman, and lived there from 1936 to 1941, when the mines closed again. We had to come back to Blythe. That's when they opened up a big air base and George Patton had his headquarters in Blythe and lots of guys training there. So there was a lot of work., and my father started working as a cement finisher and in the manganese mines. Racism was rampant, We always fought Gringos, and we always won. My brothers were fighters and we were a big family. We weren't pushovers.

The education department used to have Americanization schools where you didn't advance. It was just to retard you really, similar to the Indian boarding schools. They should have called them brainwashing schools. I didn't go, so that's why my thinking has been a lot different from that of my buddies, who did. Hell they were 9 years old and still in the first grade. It was just awful! When they got out of school, after 6th or 7th grade, they had to pick cotton. I barely picked cotton one day in my - we were always in the mines. My buddies that worked picking cotton didn't go to school. and my mother was always very adamant that we go. Blythe had its high school since 1916. When I graduated, just 5 Chicanos graduated with me out of around 100 students. When I entered that high school in 1947, only 4 Chicanos had graduated in all its history.

We were the majority of people in town and the Blacks were a small minority. But more Blacks graduated from school than we did because they used to grade them according to how many pounds of cotton they picked. They didn't come to the school - they worked for the grower. He would say how many pounds each picked that week, and that's how they graded them.

My older brother, Mike Figueroa, was the first Chicano to work in the post office. It was a big deal! My mother would say, "My son works in the post office." And all the other ladies would say, "Ooohhh!" But my father criticized the hell out of Mike. "You're gonna be a domestic slave! You're always gonna have that damn yoke on your back," he'd say. "This is one of the worst things you could have ever done." My brother had just graduated from high school, and at the time we were making a living by making charcoal out of iron wood, something we used to do in between times in the mines. We were making ovens out of 16 cords of wood - like little mountains. So my brother got mad and threw his axe away. Mike said, "I'm gonna go to town and get me a job!" And my father said, "You know nobody is gonna give you a job!" Because they didn't give Mexicans a job - nobody worked in town. You were supposed to work in the damn fields. That's why my father was so independent - because working in the mines you're your own boss. So Mike started from one end of town and went all the way up, putting in applications. Finally he landed that job in the post office. My brother was a brain - he was the only male who knew how to take short hand. When he took the civil service exam he passed it with flying colors.

DB: You guys really had to fight for everything.

But we were always on the winning side. We always won. My other brother Gilbert was el asote - the guy with the big blow. My brother never lost a fight in Blythe. You didn't mess with the Figueroas. When Mike was a small kid the teacher would come and say, "Okay children, it's recess." But Mike didn't go out. They'd say, "Well, Mike doesn't play." That was a joke that was all over town. Mike had run ins with cops and immigration officers, and he'd always take care of business. He used to criticize me for getting involved with Cesar Chavez and this non-violent business. But my character's a lot different. He's fortunate that he's never been shot or incarcerated. Oh he was incarcerated one time when he was fighting with my brothers. The cop took him to jail and they were 12 years old!

When I was a small kid in 3rd grade we were starting geography. The teacher pointed to a map on the wall and said, "Now this is the United States that we all love so much." I got up like an Indian and raised my hand and said, "Well I don't love it too much." She asked, "What do you mean? You don't know what you're talking about!" I said, "My father says they stole this land from us." I wouldn't change my mind, so they sent me home and told my mother I was unpatriotic. They kept me away for two weeks. They took me to the principal's office, where he had a big old paddle they used to call the board of education. And they paddled and whipped me. They made a play named after Philip Nolan's book, Man Without a Country, and showed it at school, just to intimidate the Mexicans. They named it Boy Without a Country. I was just telling them, "This is my land." I was just a little kid. Can you imagine, 9 years old? Man! But that's why they had the Americanization schools, to brainwash all those young Mexicans and Chimahuevos living in Blythe.

My mother always used to say that we were Chimahuevos and my father was Yaqui. We never did classify ourselves as American. Never! It was a battle everyday, and we knew who we were. My mother negotiated with the principal, and I had to write on the blackboard, "I love the United States" in front of all the kids a hundred times. And then I was accepted back as a student at Blythe grammar school.

|

|

Caborca, Sonora 10/24/01 The front of the mission church in Caborca, built by Padre Kino. The bullet holes are still visible from the attempt by William Henry Crabb to take Caborca and northern Sonora from Mexico in the 1850s. The town's residents took shelter in the church, defeated Crabb, chopped his head off, and displayed it in the church tower. |

DB: So part of the reason for your family's attitude came from the fact they were miners?

Yes, mining gave us a lot of independence. But the workers who worked for the big mines were not this way. We had a big mine in Blythe, United States Gypsum Company. My father and his friends could never get a union going there. Some of the guys had been working there for 30 years. They had the company stores there. All the houses were owned by the United States Gypsum Company. And the people were just like property of the mines too. Once, when my father was working there the foreman came and said, "Hey Figueroa! How come you're not in there?" My father said, "Well, you go in there." The foreman answered, "No. It's too dusty." My father told him, "That's exactly why I'm not in there! Because I'm not gonna leave my lungs there! I left them already in Arizona and I'm not gonna do it no more! You put some water in there!" You see, when they were drilling they never had water to control the dust, so the guys used their bandanas when they were working down in the shaft or in the tunnels. It was dusty as hell! Water would stop the dust, but they didn't want to do it.

The unions were going all over Arizona - the Mine Mill Union - but not in California. My father used to say the miners there were just dominated by the bosses. But they used to pay a lot better then working in the fields, so they thought it was a damn good job.

|

|

|

|

El Voludo, Sonora 12/5/02 The home of a gambosino, a placer gold miner, in the desert at El Voludo. |

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 Guillermo Bovey turns the crank on the polveadora. Bovey is one of only a handful of people here who still make a living from mining gold in this way. |

|

|

|

|

|

El Voludo, Sonora 12/5/02 Filomeno Murrieta looks for gold dust in the polveadora, the traditional wooden apparatus used by gambosinos to separate the heavy gold dust from dirt and rocks. |

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 Guillermo Bovey and his son Samuel Othon. Othon comes to stay with his father to keep him company, but lives in Pitiquito, a large town near Caborca. |

DB: What did the border mean to your family when you were growing up?

People would come to Caborca because there'd be big happenings there. They would just migrate back and forth. It was two to one, the dollar and the peso. But after the war, things started changing a lot. It started with the money - eight to one, twelve to one. Then it got, I don't know how many hundreds to one and you needed a wheelbarrow to exchange. But in those early days there was more difference between Sonora and southern Mexico than Sonora and Arizona. In Sonora and Arizona they eat menudo blanco. In the south it's red because they put chile in it. In Sonora people eat the flour tortilla. In the south it's all corn. It's not so good for us. The flour tortilla really gives you diabetes, but everybody loves them. Padre Kino got people started growing wheat, and that's what changed it. Even our language is more similar than we are to the south. Sonora and Arizona - we're all the same people. Even the Treaty of Guadalupe and the border didn't change the custom. We have the same food and the same manner of speech. We use a lot of words that blend Spanish with Opota and Yaqui. And people from the south don't understand that. All the mining terms here are mixed like that, and everybody here was a miner.

|

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 The Danza Azteca Cuauhtemoc group from Nogales, AZ, perform during a march and caravan down the main street of Trincheras, celebrating the birth of Joaquin Murrietta. |

DB: What were the differences between miners and farmworkers?

The miners were sort of the elite. A miner always had a damn good shoe and a damn good hat. Friday, Saturday, and Sunday they'd get decked out and do their thing. On the farms, they were always domestic slaves. I used to have a service station where I saw the injustices people suffered. At that time we had 5000 Braceros in Palo Verde. The growers association was right there in front of us, where all the workers would come to get paid. Then they would cash their checks at our service station. So I would see their checks - zero, zero, zero. The contractor would charge them for everything. If the grower needed a hundred workers they'd sent 200 to do the job, and the people would only be able to work half the time. Most of the time they'd spend at the labor camp, spending the little money they got. So when they got their check, it was zero, zero, zero, zero.

My brother was more involved than I was at that time. He used to get all the complaints when they'd go down to the post office, because he was the only guy that spoke Spanish. So we became involved in politics at that time. We used to call the Mexican Consul about the violations. He'd come down, but before he got there they'd clean the showers. They'd put clean sheets on the beds and give the workers a steak dinner. Then the guy would say, "What's wrong with you guys? There's nothing happening here. Everything's good."

In 1960 they started big strikes with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee down in Calexico, and we went down there. They wanted to continue the strike when the harvest came to Blythe, and then Salinas. I was going to be the organizer in Blythe, so we went to Imperial Valley to get involved with AWOC. At that time, Mexico was supposed to get one million five hundred thousand acre feet of the Colorado's water. Out of the river's fifteen million acre feet of water, seven states get water from the Calorado, plus Mexico. But Mexico never has gotten it's share. In addition, the river's water was too alkali, because they were opening the Gila River watershed, and using the river to wash all those lands. When they flooded the land, the alkali rose, and was drained through the ditches, down to the river. The whole cotton crop in the Mexicali Valley grew less then 18 inches high because the water was so salty. Every time farmers would irrigate in Mexocali it would ruin more of their crops. My cousin Oscar had a big ranch there and had to leave it. So on the Mexican side at this time people had a big issue, and on our side we had a major issue about the braceros, and the way they were being mistreated. They began to call big meetings between the small farmers from the Mexicali side and us in the AWOC from the California side to try to talk to each other. We'd meet right at the border.

Kennedy had just been elected. He called Al Green, the head of AWOC out of Stockton. He asked AWOC to stop the strike because they didn't want to create an incident in the border when Kennedy had just come on board. We couldn't win the strike anyway because of the braceros. When we would try to advise them their rights they were deported. So Robert Kennedy stopped the strike. He did some good things, but in that incident he didn't. I didn't stay too long down there cause it was too damn rough. And it was an endless fight. And right away, the whole effort was closed down because we didn't have the support of the AFL-CIO any longer. What the hell were we doing out there? So I just went back to Blythe.

When we came back, the growers already knew we'd been in the Imperial Valley. They took us to the Farmers Merchant Bank. You should have seen the third degree they gave us. They couldn't give me much trouble because I didn't work for them. But Mike worked in the post office. So they said, "What are you Figueroas doing down in Imperial Valley? Don't you know everybody there has guns? We have a real nice atmosphere here in Blythe. I know your father, and your mother, your grandmother. Why would you want to go down there? If you guys need a job, or you want to get a loan, we'll give you one." The Farmers and Merchants Bank was the big bank in Blythe. The head bank people were all growers. I didn't give a damn, but my brother was fired from the post office. But he sued them in 1960 and won. And that's one good thing Robert Kennedy did - he fought for my brother. One day Kennedy called him at 2 o'clock in the afternoon and told him his case had been settled. They finally gave him his check in 1963, and it was a big one.

Then the cops beat the hell out of me in 1963, here in my hometown, on our street. They dragged me from one of my favorite bars. I was in the El Sarape Cafe, right beside the place where we later had the union office. And I was singing to the owner. I'll sing anywhere. No big deal. But here come these three cops and they thought I was drunk. I was actually drinking a 7-Up, just getting ready to go home after I had finished eating. So one cop, who didn't know beans about Chicanos, says, "Those guys are crazy as hell. Look how they're carrying on!" So they said to me, "Oh, you want to come outside." I said, "Hell no, I'm not going to come!" Because I knew what would happen. "You know you guys are barking up the wrong tree," I said. But they thought I was a smart ass bracero who knew a little English. And right there, they grabbed my arms and my legs and threw me against the bar. Then they handcuffed me and threw me out of the door. My face hit the sidewalk, and they dragged me to the car. Then they kicked me and tried to wedge me into the back door. I said, "This will be the last Mexican you'll ever kick!" They laughed at me. "That's what all you guys say!" But we had a new judge in town, and that changed everything. I won my case and then I sued them. And I was the first Chicano in the United States to win a police brutality suit.

That turned my whole life around. I said to myself, okay gringos, here we come, with facts and figures and organization, to get people to register and vote.

There was a lot of animosity against the braceros at that time, because the growers wouldn't give jobs to the local Mexicans. Finally they passed a law that said that growers first had to deplete the sources of local workers. That's what they used to call us - the locals. Then, if they didn't find enough locals, they could hire braceros. But you know, they never did that. Finally, the braceros all were returned in 1964, on December 31st. To this day we're still trying to get the 10% of the wages due to the braceros that was withheld while they were working, but never returned to them when they finished their contracts from 1942 to 1964. If it hadn't been for MAPA (the Mexican American Political Association) and Bert Corona, Public Law 78 and the bracero program would have been extended. But thanks to our efforts, we were able to stop that damn law. And as soon as that happened, in 1965 , AWOC and the Filipinos struck. Just like it says in the song, "el dia ocho de septiembre de los compos de Delano salieron los Filipinos." And if it hadn't been for the Filipinos beginning that strike, Cesar wouldn't have gone on strike either, because he thought the time was not yet opportune.

There was nothing happening during that span from 1960 to 64. Cesar was organizing the Association, trying to make contacts, but nothing major. I knew Cesar in 1949. Cesar got married in 50 to Helen Favela, and her sister, Teresa Favela, married our next door neighbor in Blythe in our neighborhood of Barrio Cuchillo. So naturally when we used to go pick grapes in Delano every summer, we'd see Cesar and his family. All the family would work, and we were teenagers. We'd work in the watermelons too. I've been pitching watermelons all my damn life, since I was ten years old. That's how we got to know Cesar. And when Cesar began the association, people started to say, "Hey, remember Cesar? Well, he's starting a union - Mexican union." The guys from AWOC were making $125 dollars a week at that time, and they used have a 1960 car. Now this Mexican, Cesar, is going to start a union and fight these growers? So, I went to meet with Cesar in Santa Barbara and started working together in the beginning of 1966. The grape strike had already started.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 The Banda de Genaro Dominguez performs during the fiesta celebrating the birth of Joaquin Murrieta. |

Joaquin Murrieta is the grandfather of our Chicano movement. He was the one that intervened right after the treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo, which was signed on February the 2nd, 1848. All my life I knew about him. Joaquin Murrieta is a symbol, as important to us as Cuauhtemoc, the last of the Aztecs. When Cortez landed, Cuauhtemoc said "The sun is gone from our sight. It's become obscured." He said that on August 12, 1521. And on August the 13th he was captured - the most sacred day of the year in the Aztec calendar. Now, after all this time has passed, we are learning the truth. And why has the time come now to tell it? The story of Joaquin Murrieta is part of the whole transformation of our way of thinking. People now want to learn the truth.

The Chicano movement just didn't start in the 60's or the 50's. Chix-Zanotl means vanguard in Nahuatl - vanguard of their treasures. Gradually over time it became bastardized to Chicano. And the name kept appearing - Zapata's main escorts were called Los Chicanos. When Hidalgo started the movement to become independent of Spain, he used the name of los Chicanos too.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 A dancer from the Danza Azteca Cuauhtemoc group from Nogales, AZ. |

|

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 Dancers from the El Quinto school in the Mayo community of Etchojoa, Sonora, perform the Pascola, a traditional indigenous Mayo dance. The performance take place at the fiesta in Trincheras celebrating the birth of Joaquin Murrieta, who was possibly of Mayo descent. |

I never read a book about him until 1958. Everything I knew of Joaquin Murrieta was oral history. When I was ten years old I could sing the Corrido of Joaquin Murrieta. And in 1975 I was taken to Washington DC where I sang the corrido with my daughters and sons.

In the early 1900's my grandfathers were thrown in jail in and Parker because they sang the Corrido of Joaquin Murrieta. My grand fathers were very proud of being descendants of Murrieta, so they would get drunk and start singing the song. The sheriff spoke Spanish, and he knew what they were singing, so he would arrest them because it was against the law. You could not sing El Corrido de Joaquin Murrieta - it was outlawed in California and Arizona. They were prohibited from singing that song on the radio too.

We have a saying in our Association of the Descendents of Joaquin Murrieta. We have to know who we are. We have to know where we're going. Once you're on solid ground, you'll go forward. Nothing will stop you. If they bump you off it's no big deal. Joaquin Murrieta is the symbol of that spirit. People now are not afraid to say they're descendants of Murrieta. That's been my greatest satisfaction. I've invested years of organizing these fiestas in Las Trincheras, where he lived and the Murrietas still live. The thing was to make people understand - there was a Murrieta. We did fight. He wasn't just a murderer, but someone who would fight for justice. He was trying to raise an army. They portrayed him as a horse thief, but he was trying to get 2,000 horses for 2,000 men, to form a cavalry and join with the Californios to take over California again. They were very dissatisfied after the foreign miner's tax was enacted in 1850. That was the law that broke the camel's back. If it hadn't been for that, the merging of the two cultures would have been a lot easier, instead of the hostilities that took place during the early 1850's.

That's why they never could find him. Every house that was Sonoran knew him, or was related to him in some way. They harbored him and protected him, up and down the state of California. He was always incognito as far as the authorities were concerned because he had so many allies. These people just tried to defend what was theirs, but to do that they had to organize a clandestine movement. They had no choice. That's why Murrieta was tried and sentenced without the authorities ever knowing who he was. And he had this kind of support because the Sonoran miners were all from the same area. They knew each other. Eventually, the great bulk of them went back to Sonora. They left the upper part of California because the law kept them from working their mines. They didn't want to suffer the consequences of staying, and the consequences were that they would kill you. The names on the lists of the people hung by the vigilantes in the goldfields of those years are all Spanish. So when they killed these people, the rest just left voluntarily. That was the agreement. If you left voluntarily, you could leave freely. But if you stayed, you were going to suffer the consequences. The first woman hung in California, in 1853, was named Juanita. According to the last California Ranger, William Howard, her last words were "Viva Joaquin Murrieta!"

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 A performer from the El Quinto school in the Mayo community of Etchojoa, Sonora. |

DB: So what impact did learning about Joaquin Murrieta have on your own ideas?

I realized that we're one people, whether we live in Arizona or California or Sonora - one continent, one world. I'm anti-nationalistic borders. To me, there's no such thing as a new world and an old world. That's the truth of the Murrieta legend.

Today there's a resurgence, and people are very proud. Everywhere you go in Trincheras they'll say, "Viva Joaquin Murrieta!" The teachers in the schools have more information, and students make plays about him. They named the main street Calle Joaquin Murrieta. From California we brought 10,000 dollars worth of medical supplies to the local clinic, and I was able to negotiate with Blythe Ambulance Services to donate an ambulance. Up north in California they've started Joaquin Murrieta Day in Mendota, in the San Joaquin Valley, where his group was ambushed on July 25, 1853. Avenue 63 there was changed to Joaquin Murrieta Avenue. Eventually we want to take a caravan of horses and riders all the way from Mendota to Trincheras, across the border. If we can get both governments involved we can probably do it. We already have permission from the big ranches along the way, and we know where the old trail used to go.

One of our goals is to have the state government of Sonora declare Murrieta's birthday a state holiday. It's not just a symbol with no meaning. I think it's going to change people's whole attitude about how government policies and educational institutions apply to them. It contributes to peoples' well being, because they realize that our history, the basis of our traditions, wasn't something false or blind, but based on hard core facts. We want to rescue our history from the lies our governments have told us for so long. Our history isn't just something from an academic publication, but traditions taught from early childhood that help us understand what life means, what it stands for.

Mexico is nearly as bad as the United States. It has a constitution that supports workers and campesinos, where the word labor appears 36 times. The United States constitution doesn't have one word about workers. But in Mexico, they don't enforce it.

In some ways, Mexico's just a stepchild of the United States. And the problems between the two countries go on and on. The other day we had a ceremony in Holtville, remembering the 600 undocumented people who died last year trying to cross the border. Many are buried there in the Holtville cemetery, and no one knows their names. John Doe, John Doe, John Doe. Can you imagine? They were trying to cross the desert, just like the miners did from Sonora, 150 years ago.

Have you seen the concrete ditch along the border in Tijuana, with the iron plates sticking up with the razor wire on the top? The racial discrimination and hostility against Mexicans is still the same but in a different day. Who brought the National Guard down to the border, and who built that damn wall? So things haven't changed so much after all. These things were happening in 1848 and they're still happening right now in 2001.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 10/23/01 A worker with his shoeshine equipment looks for customers during the Trincheras fiesta. |

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-